Some views of the church over the last two centuries

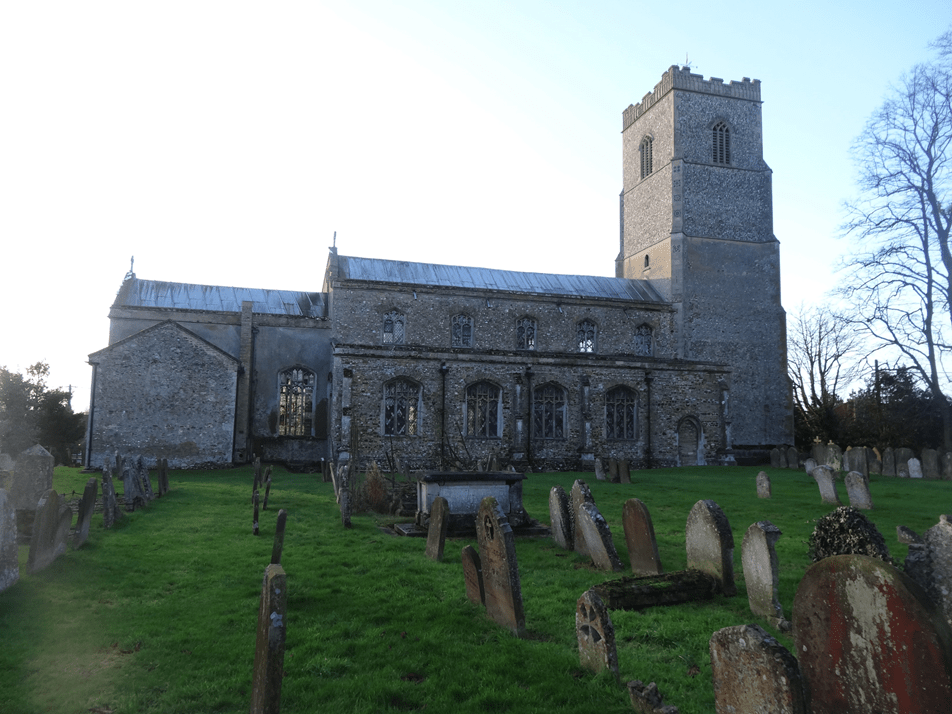

St. Martin’s today. Take away the War Memorial and cross and it is a view fairly unchanged for hundreds of years.

Apart from the vestry which dates to about 1500, and the tower which was built in stages to the end of the fifteenth century, St. Martin’s is a church built in one go around 1430. Inside as well there is very little structural change from that time.

Drawing by Elizabeth Jones c.1806

Taken in 1901 by Henry Walter Fincham who was a well known professional photographer. His surname is interesting!

From a postcard stamped in 1906. The trees certainly spoil the view of the building!

The lithograph from Blyth’s book of 1863 – which is supposed to have been done c. 1840. It shows the clock which was installed in 1844 so it is post that date. The roadside wall is the same as it is now. The buttresses have certainly been effective. The people seem rather small!

Robert Ladbrooke print from the 1820’s. The chancel doesn’t seem to be rendered.

Ladbrooke was a leading member of the Norwich School

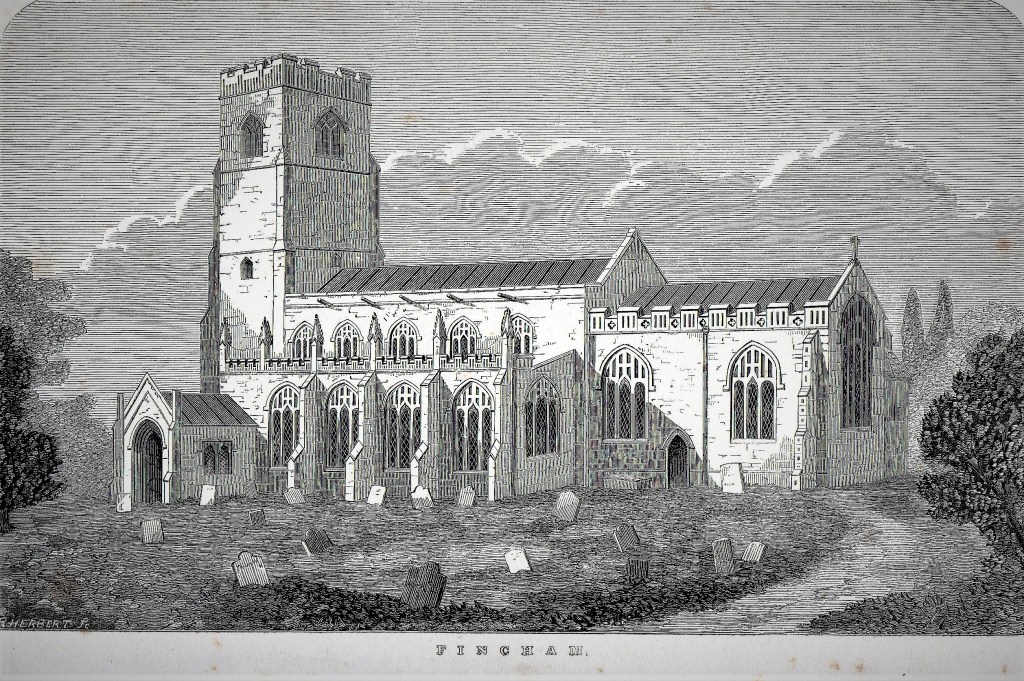

R Herbert -wood engraving on paper from early 19th century. The chancel not rendered.

Probably taken early 20th century

The north side of the church today showing the vestry.

*********************************************************************************

The Vestry built c.1500

The wonderful churchyard wall in early 21st century, listed Grade 2, and hundreds of years old.

****************************************************************************************

An account of St.Martin’s in 1860

********************************************************************************************************

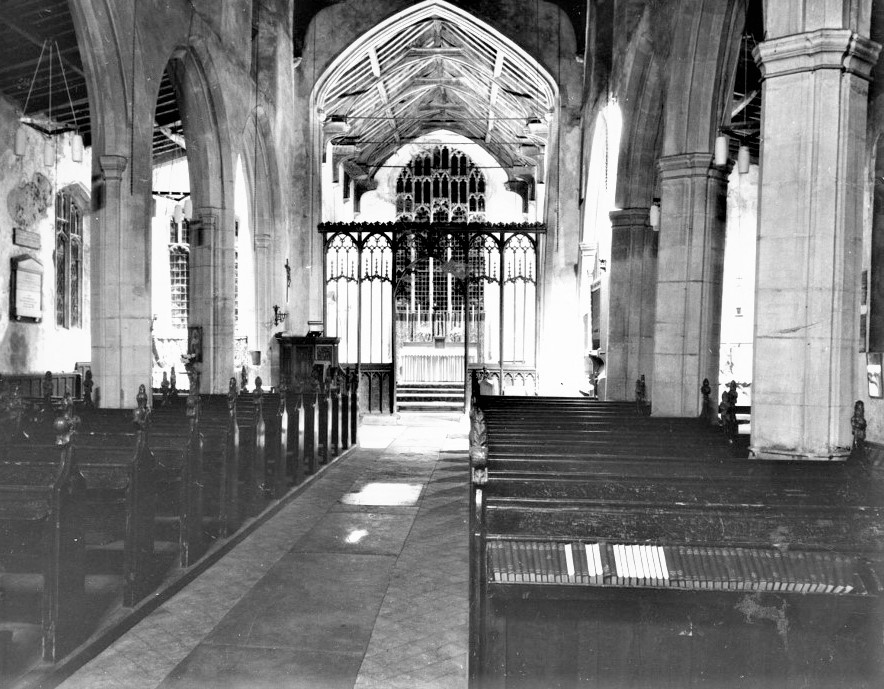

Some interior views

The pews in the foreground have now been removed and are possibly those now (2024)in the south aisle. near the door.

The old font base which is now the pulpit base has the alms box on it.

***************************************************************************************************

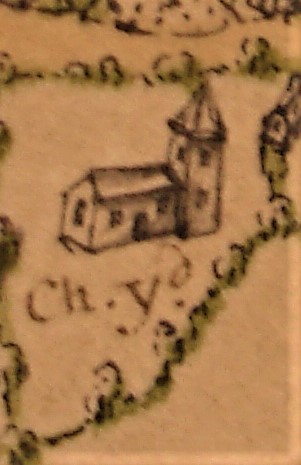

These are the drawings of the churches on the Hare Map of 1636. The first also shows the Rectory of St. Michael’s. Whether any attempt was made to accurately portray the buildings is anybody’s guess. Certainly St. Martin’s looks the wrong way round with a door in the north side and no chancel or vestry, which we know dates to about 1500!

************************************************************************************************************

St. Michael’s & St. Martin’s Churches Fincham

Early records

The Domesday Book

In 1858 the Rev George Munford, Vicar of East Winch, and a member of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, published a work titled ‘An analysis of the Domesday Book of the County of Norfolk. In it he says Fincham was one of 17 churches recorded in the Clackclose Hundred ( although many churches were not recorded). The survey gives the ancient name Phincha, the modern name, Fincham, and the ‘Tenant in Capite’ who was one Hermer de Ferrariis. A tenant in capite was one who held land directly from the Crown. Munford says ‘Hermer is conspicuous in Domeday Book as being by far the largest unlawful invader on the lands of the freemen of the county, and was probably one of the most violent and tyrannical of the powerful Norman barons who accompanied Duke William to England.’ He was given 25 lordships in Norfolk by William 1 but took many more by force-or probably just the threat of force. His heirs were the Lords Bardolph of Wormegay. Blyth gives details of more ‘tenants in capite’ who received lands in Fincham from the Conqueror. The main beneficiary was William de Warren, Earl Warren, one of the king’s most powerful followers who built the castle at Castle Acre. He had 139 lordships from the king in Norfolk alone. He had 375 acres in Fincham.

So Fincham had at least one church in the 1080’s at the time of the survey. It is just possible there were two churches as only a small number of churches were recorded in the survey. However it is almost certain that the church referred to was St. Michael’s, now demolished. When demolition took place in 1745 the font was moved to St. Martin’s and that font is certainly Norman, if not Saxon, in origin. There survives on the St. Michael’s site a large boss, considered Norman in date.

Description of St. Michael’s

There is a description of St. Michael’s in Blomefield’s History, published about 1760. It was ‘built of flint and boulder and consists only of a nave, or body, with a chancel covered in lead. At the west end of the nave stands a large square tower embattelled with quoins and copings of free-stone, and a pinnacle at each corner; and herein hangs three bells. The length of the nave is about 60 feet and in breadth about 27feet The chancel is in length about 33 feet and in breadth about 18 feet also a little freestone porch or passage into the chancel; in the centre of the arch there seems to be cinquefoils cut, the arms of the Lords Bardolfs.’

For comparison that nave is just under half the size of St. Martin’s nave.

Two churches

So, at an unknown date and possibly sometime after the Conquest a second church, St Martin’s, was built. The first incumbent mentioned in the list given by Blyth, based on Blomefield, is Edmund Bardolph who became rector in 1294. This does not help with dating the building of St. Martin’s. However Blyth gives some indication of dates. In his history of Fincham, he quotes a fellow clergyman who saw evidence that some windows we see now that are Perpendicular in style are insertions within earlier Transition and Decorated work. This was the Rev. E.Blencowe, Rector of West Walton. According to Blyth he was a person ‘whose acute observations and practised eye detected similar evidence all round the church.’

Transitional refers to the Norman Gothic period of 1066-1200 when many buildings still had thick piers and rounded window openings of the Romanesque style. They had simple vaulting and decoration. So it is probable that St. Martin’s was built not too long after the Conquest. It is on a much more prominent site in the village than St. Michael’s.

Thus it is likely the two churches existed, less than one hundred yards apart, from at least sometime in the 1100’s until 1745..

Many generations of villagers worshipped at one or the other for about 600 years. The Black Death, Reformation and Civil War came and went. There are references to the Fincham family having specific association with St. Martin’s. Adam De Fyncham, who was Attorney General to Edward 11 and Edward 111, was buried in St. Martin’s Church in 1338. Simon Fyncham made bequests in the 15th century to the rebuilding of the church in the Perpendicular style. Nicholas Fyncham restored the Vestry and was buried in it in 1503.(Blyth)

Rectors and Vicars.

Blyth lists the incumbents of both churches. He used the lists in Blomefield and did his own researches to check their accuracy. Both lists start in the 13th century. St. Michael’s in 1253 with one Jeffery de Derham (although he does mention John de Palgrave as having preceded Jeffery but with no date) and St. Martin’s in 1294 with Edmund Bardolph. Both were Rectors. The advowsons -the right to grant the living- was initially in the hands of the Prior of Castle Acre (St.Michael’s) and the Bardolph family (St.Martin’s). Rectors could collect tithes as their income.

St. Michael’s incumbents remained as Rectors until the church was pulled down in 1745.However around 1345 John Lord Bardolph granted the advowson of St. Martin’s to the Prior of Shouldham Abbey. The abbey decided to have the tithes paid to them directly and the living became a Vicarage. The Vicar was to have ‘’a convenient dwelling and £10 per annum.’ Until 1745 the incumbents remained as Vicars.

The Reformation meant the end of Shouldham Abbey. Henry VIII gave the advowson of St. Michael’s to the Duke of Norfolk. In 1545 the same person, Thomas Freke, appears as both Rector of St. Michael’s and Vicar of St. Martin’s. This arrangement with one or two exceptions continued until both livings were consolidated in 1745 when the smaller church was pulled down.

In 1744 an Act of Parliament was obtained consolidating the Rectory of St. Michael and the Vicarage of St. Martin’s and allowing the demolition of St. Michael’s. It is recorded in the St. Michael’s Register that the last service in St. Michael’s was the marriage of the Rev. William Harvey, Rector, to Martha, the widow of his predecessor, the Rev Joseph Forby, on May 30th 1745. In a Vestry Book a payment is recorded as ‘In 1751 Henry Weasenham, for pulling down the steeple, £4 4s.’ Around the village it is likely that any piece of large dressed stone in the walls of buildings and yards came from this church. Dressed stone would have been very expensive to bring from natural stone areas. The font was moved to St. Martin’s along with a wall tablet to Rev Daniel Baker.

*****************************************************************************

An expert investigation In 2012 a group of historians from the University of East Anglia, led by Dr Claire Daunton, carried our research on the building of St.Martin’s. They reported-

‘(We are) writing to set out the findings of the group of historians from UEA who have recently carried out research on the building of St Martin’s Church Fincham.

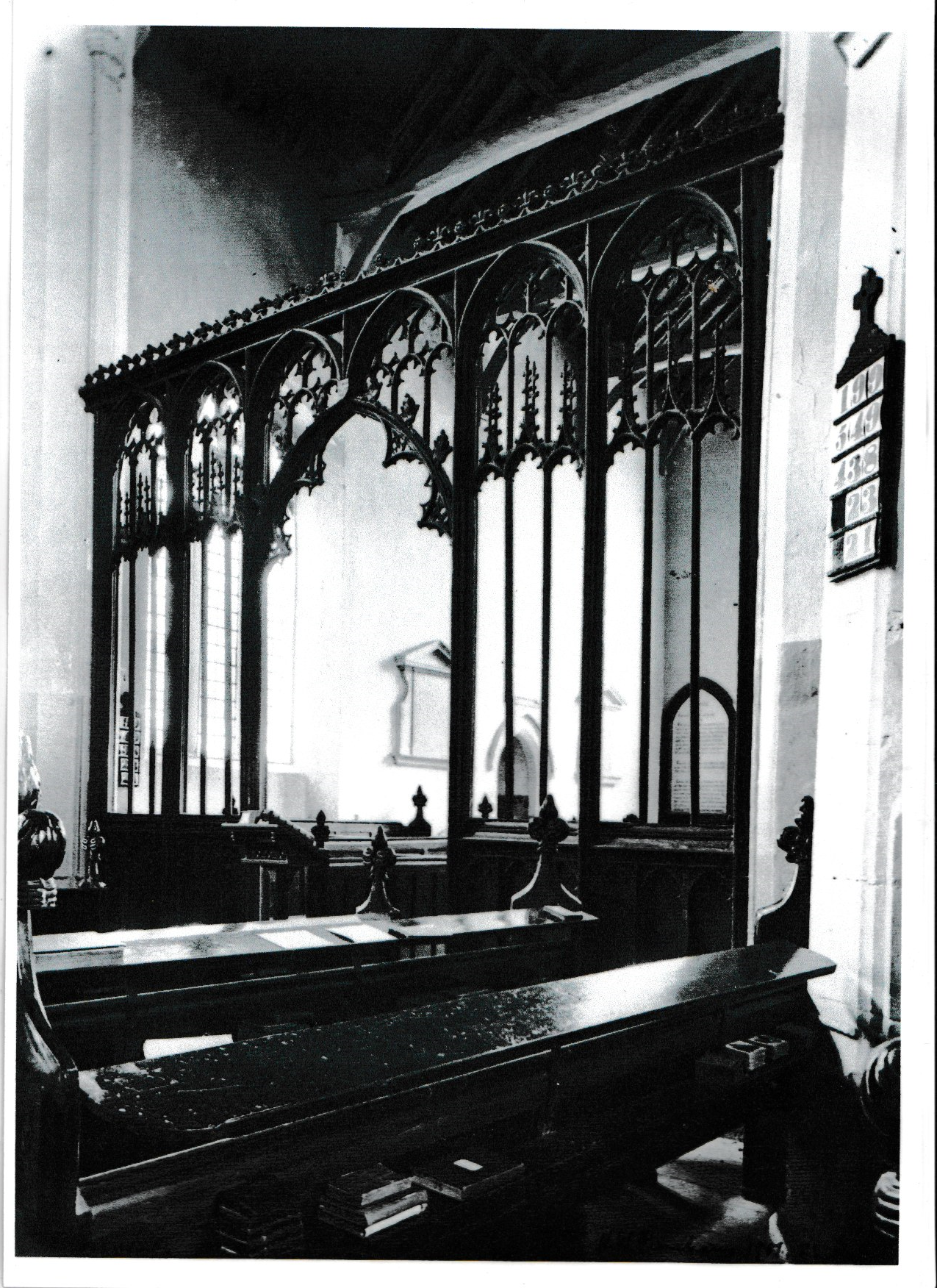

We are a group of four. We’ve looked at the general architectural style and composition of the building relative to other churches in the area where we know building work was going on in the first half of the fifteenth century. We’ve also looked in detail at the building of Fincham church using the evidence of masons’ marks and stonework. We’ve looked at the composition and decoration of the rood screen, at stained glass and at the roof carvings.

We’ve also examined contemporary documentary evidence and later antiquarian material concerning those who supported the church financially in the late middle ages.

Taking all this evidence together we believe that there was a major building campaign going on in the 1420s and 1430s, and that it was this campaign that created much of the church as it appears today. Clearly there were restorations in later periods, most notably in the mid nineteenth century, but essentially what we see today was a product of the early decades of the fifteenth century. The tower was obviously built in stages, one stage being marked by the Fincham heraldry which probably refers to the legacy left by Simon Fyncham on his death in 1458, but the tower would not have been completed until the end of the fifteenth century. Certainly there is another bequest to it in the 1470s.

Our research on the rood screen – undertaken by one of our number – suggests that much of it is original and probably dates from the same period (1430s) or perhaps just a little later, perhaps 1440s/1450s. It is very fine and there appears to be only a small amount of repair or additional woodwork of a later date. The painting is likely to be original, but without doing a scrape and full analysis it is not possible to be certain about this.

The Finchams were a leading family in area over many generations, and there is evidence that they supported both the churches of St Michael and St Martin Fincham. There were a number of leading families, of which they were probably the most active and wealthiest; others included Geyton, Shuldham, Trussbut andTalbot. There is evidence that Simon Fyncham bought up a lot of land in the area in the mid fifteenth century and his son John became wealthy as a lawyer. It’s likely that all these families put money into the

church but it happens that there is more evidence – though not a lot – for Fincham activity.

The medieval glass in the chancel shows angels playing different instruments, and is typical of Norfolk glass of the 1430s.

The figures on the roof posts are very interesting and can be compared with those in the north aisle at Mildenhall and one the roof posts at Outwell.

The connection between Outwell and Fincham is through the Fyncham family, the connection between Mildenhall and Fincham is through Thomas Barton who held land near Mildenhall and at Barton Bendish. The date of the roof decoration in each of the churches mentioned here is the same and the message of the carvings seems to be the battle between good and evil, virtue and vice, symbolised by the figures of the angels, the demons and the other figures which appear human but are distorted either by long tongues, or animal faces. The Church’s teaching on good and evil was one of the areas of basic instruction that priests were obliged to give to parishioners, through preaching and teaching, and imagery must have helped

them to do this. Figures on roofs of this type appear to be quite special to this part of Norfolk and to this particular period.’

The medieval window in the chancel has in-situ glass in the tracery dateable on style to c.1430 to c.1450, confirming this dating. This window was restored in 2014. Much original glass and leadwork was retained and the whole protected from the elements by internally ventilated protective glazing.

The wandering village cross

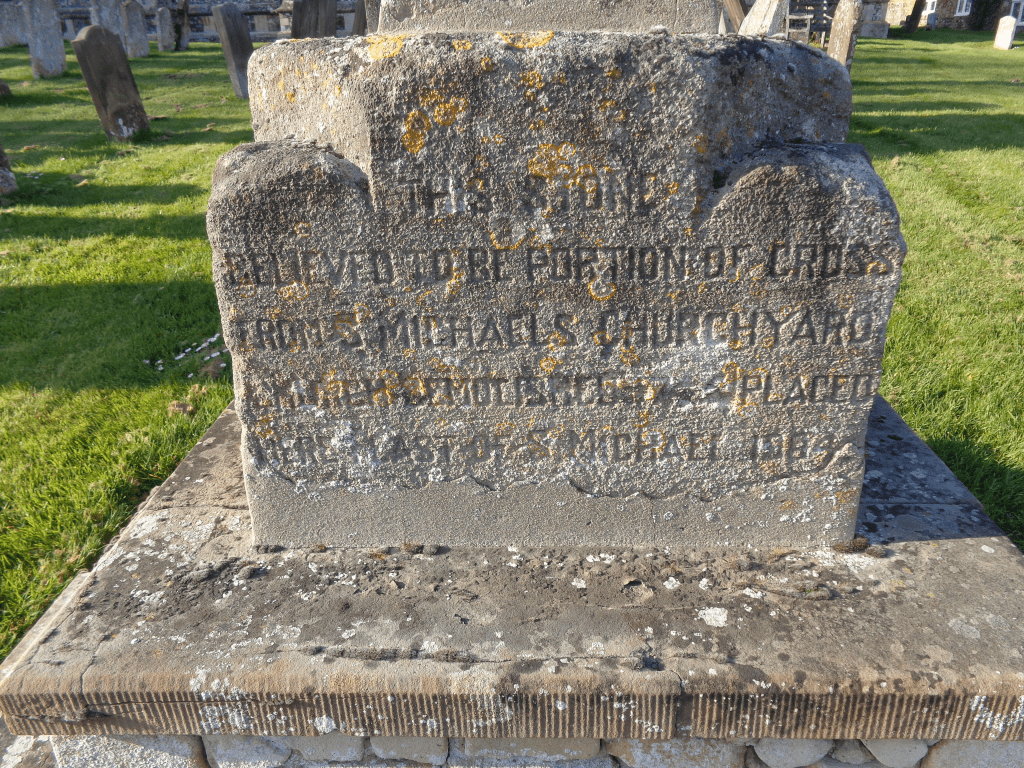

Many villages in the county once possessed a cross situated on a public highway that would act as a focal point in what would often be an extended area where a market could be held. The churchyard of St Martin’s Church retains a fragment of a medieval cross that originates from an uncertain date. The base of the fragment reads:

THIS STONE

BELIEVED TO BE PORTION OF CROSS

FROM St MICHAEL’S CHURCHYARD

CHURCH DEMOLISHED 1745 PLACED

HERE EAST OF St MICHAEL’S 1904

The weathered inscription may however reveal only part of the stone’s history. It is believed that this cross may have originally been positioned at the Downham Road / Lynn Road junction to the west of the village at a time when this was a much more open space that incorporated a large pond. If indeed this was the case, then at some point the cross was moved to St Michael’s churchyard. In 1745 the new rector William Harvey was responsible for the demolition of St Michael’s church and it was William Blyth who wrote in his diary in December 1866:

Erected last Friday (21st), in the Rectory garden, the base of the old village cross, which stood near Talbot’s manor house, where the road branches off for Lynn. It is a very hansom stone 2ft 2inches square below, and 2ft 2inches high, the upper part being octagonal from a circular pillar at the junction.

The cross base was placed in the rectory garden as a support for a rain gauge or sun dial but it does not seem to have rested there long. It was moved again in March 1875 to a new position 460m due south into a meadow belonging to the rectory. Quite why the cross was placed in this isolated position remains open to question. The cross was not located on a public thoroughfare of any sort but on church owned land remote from the village and adjacent to a pond known in the village as “the pinnacle pit”. Was the “pinnacle” considered merely an architectural feature that would act as a picturesque focal point visible only from the upper floor of the rectory, or does its position bear some deeper significance? In 1904 the cross was moved to its current location whilst the later pedestal that remained at the field site was finally demolished in 1978.

In the papers on Monday April 16th 1973