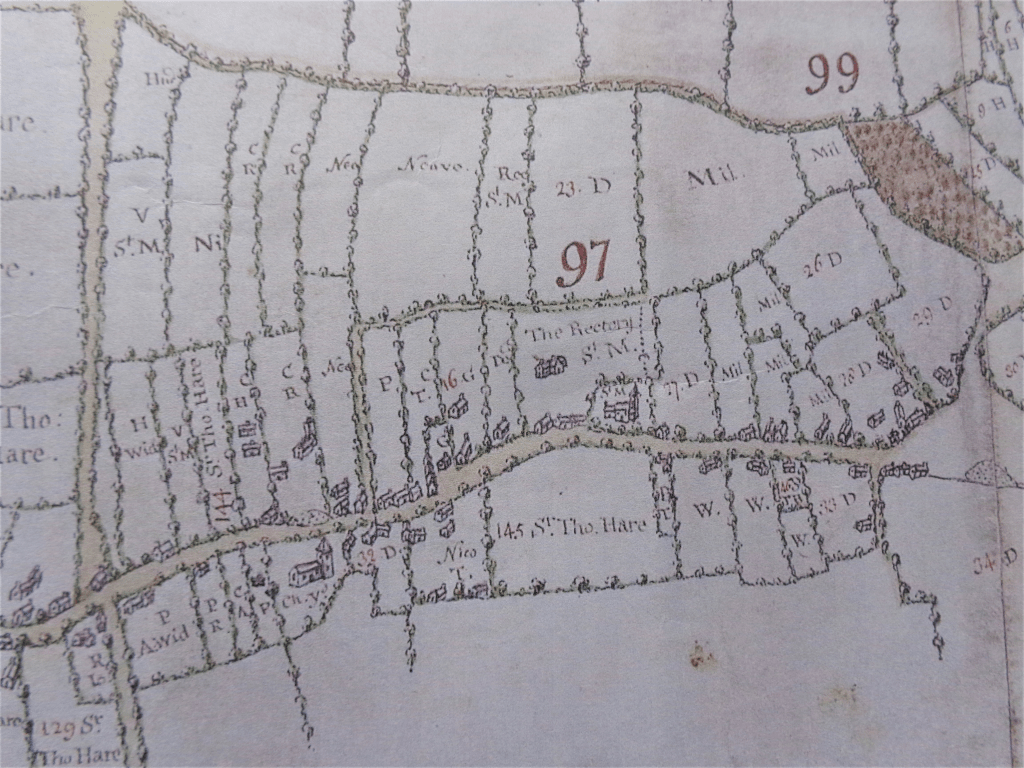

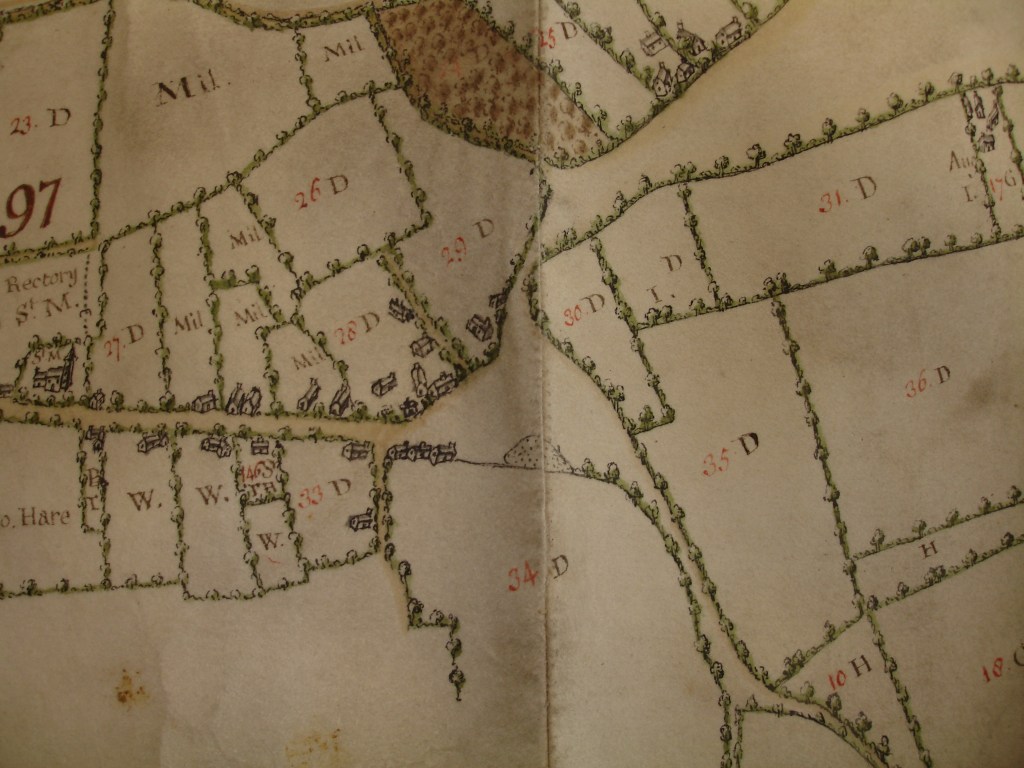

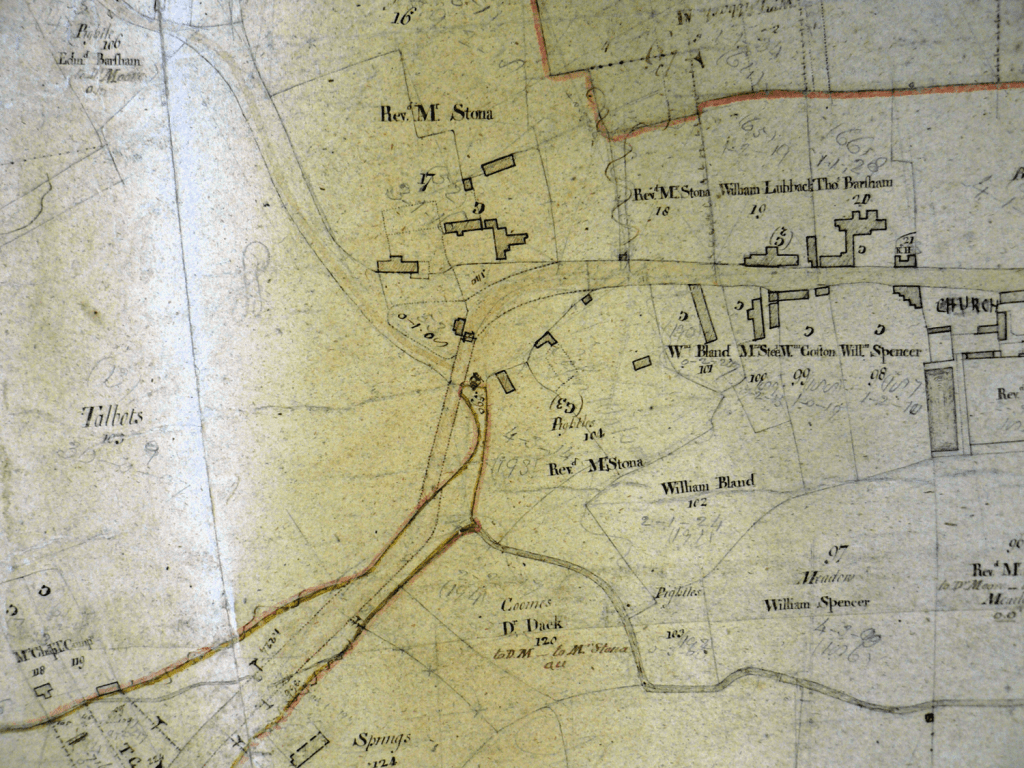

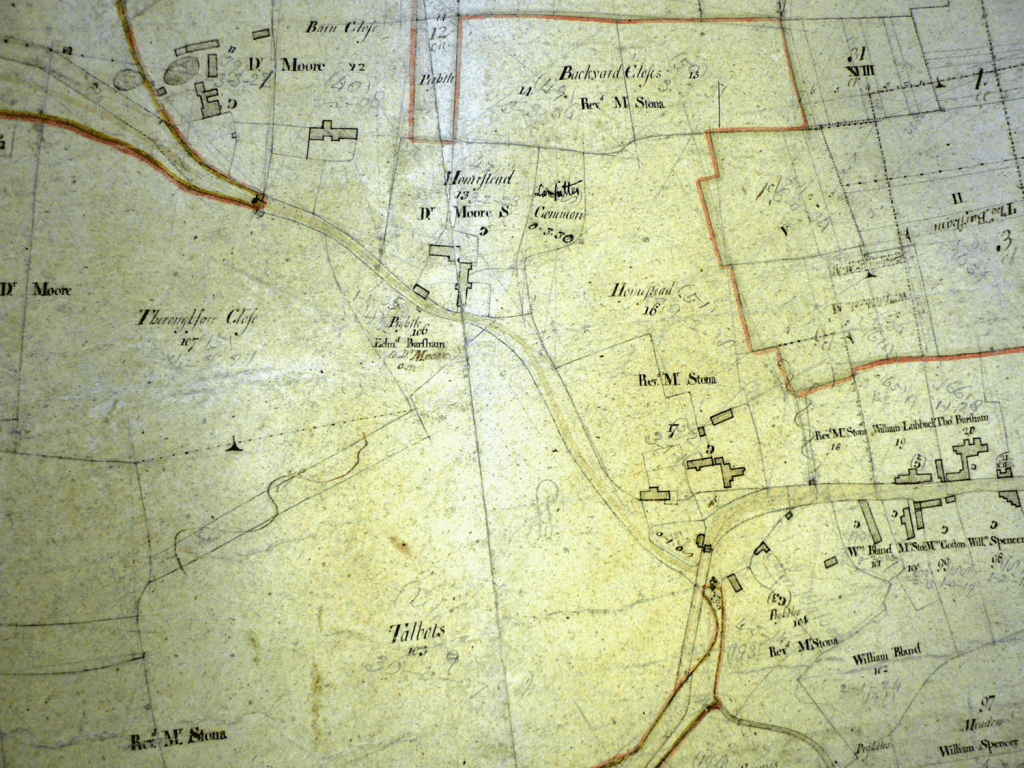

The 1636 Hare Map

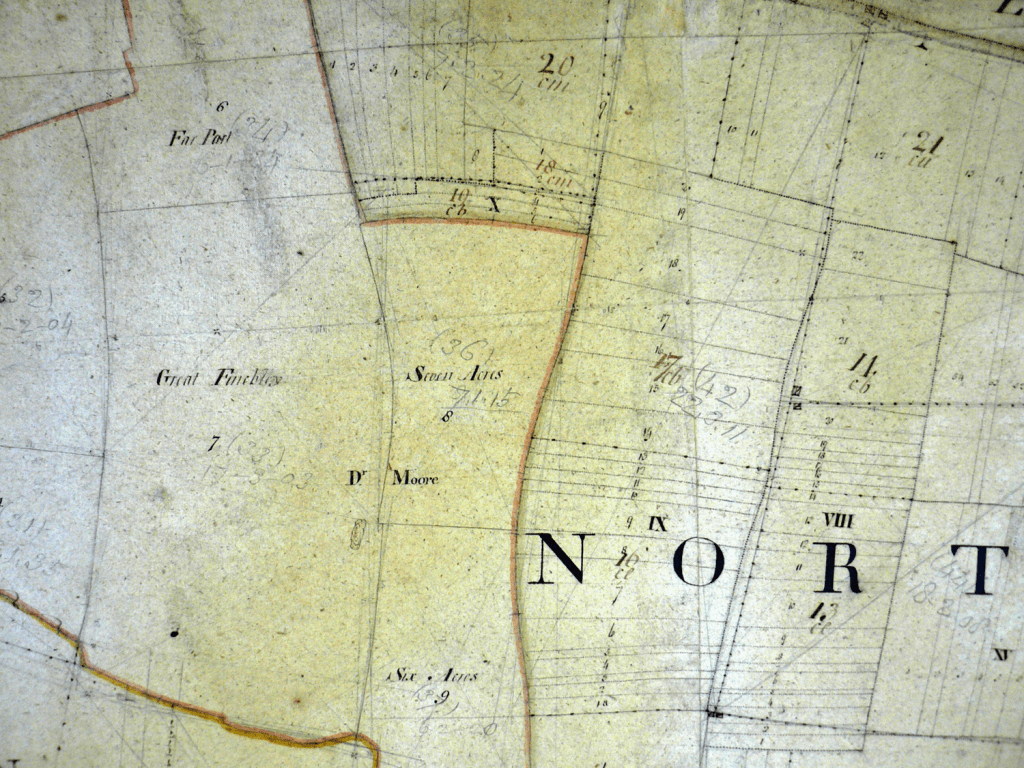

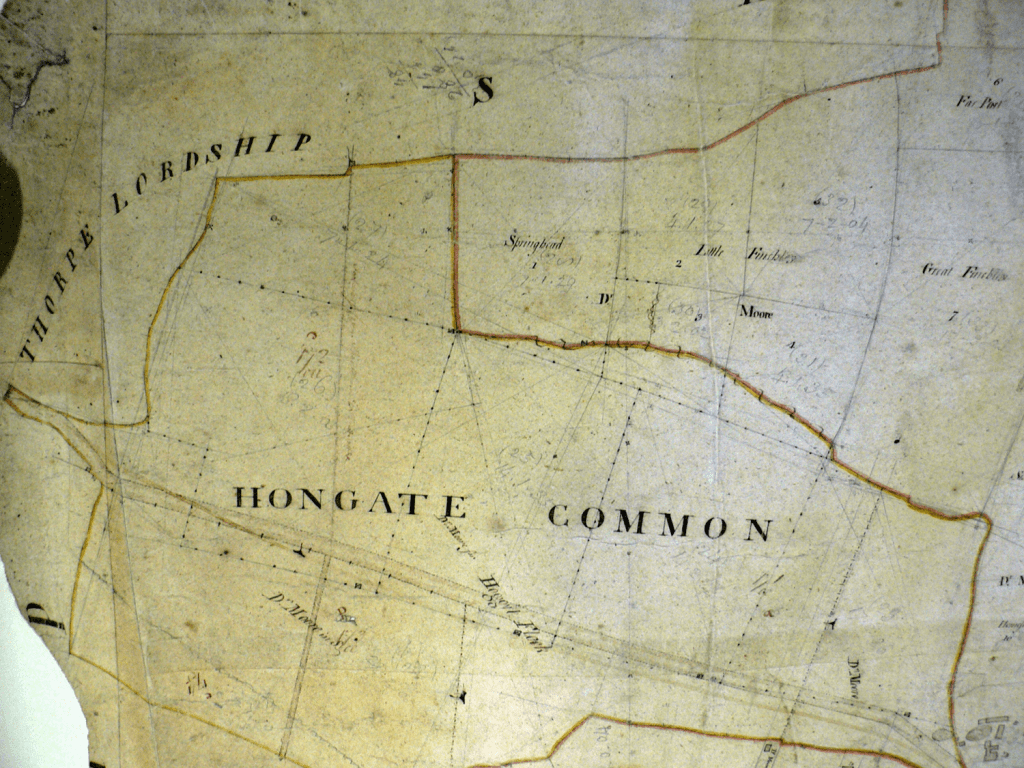

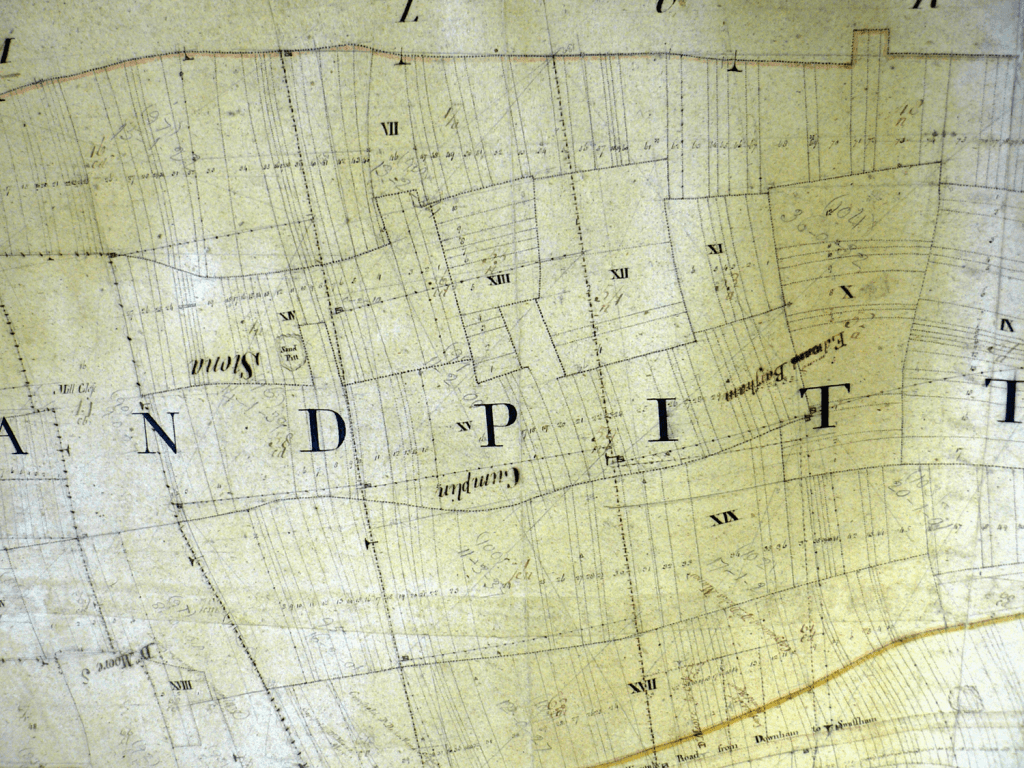

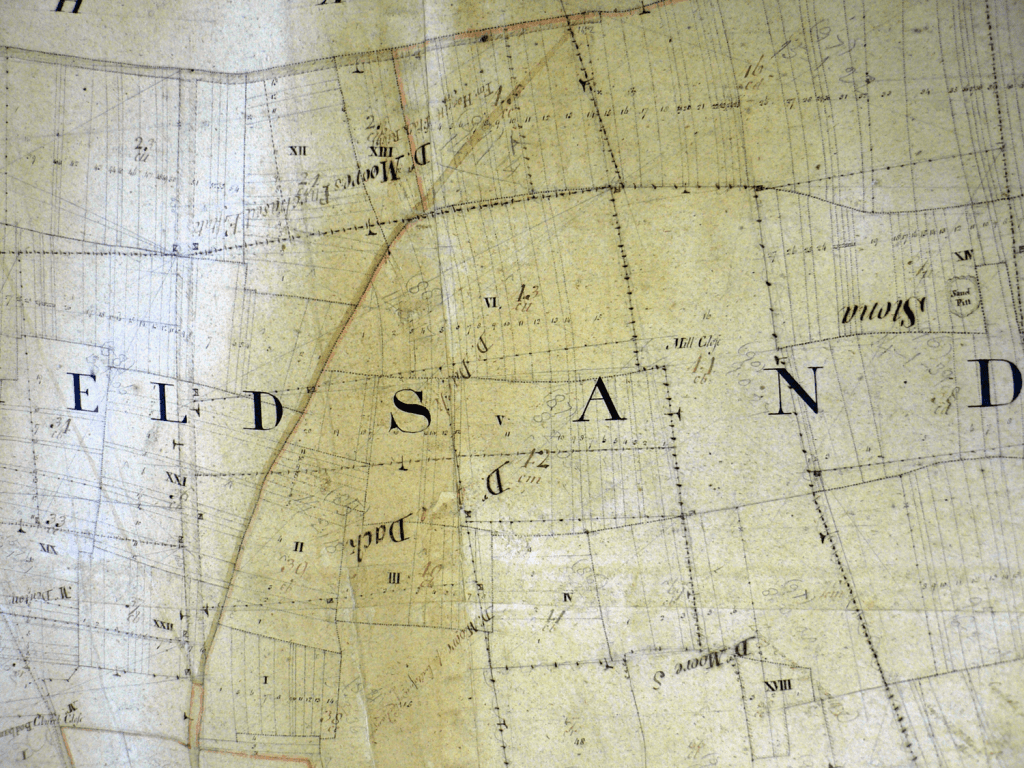

The date of this map is only approximate, but its purpose is not. Sir Thomas Hare was a deputy Lord Lieutenant of Norfolk and powerful land owner within the locality. This map, together with a field book, records the extensive landholdings of the Hare family in the area to the south of the village and it is unusual in that it is oriented to the south rather than the usual convention of the north. The document does not encompass the entire parish but does illustrate life in Fincham during the reign of Charles I.

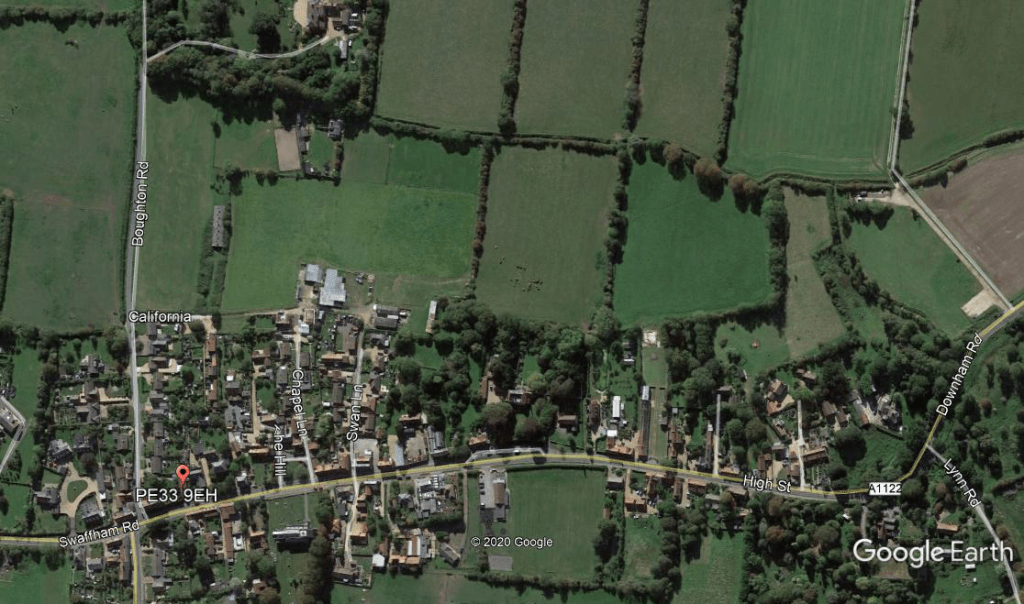

The map gives a snapshot of the area south of the village before the enclosures of the 18th century transformed the landscape into something like that which is seen today. The fields directly to the south of the village were once traversed by three tracks that have now vanished beneath the plough. The tracks gave access from the medieval patchwork of strip farms in the south east to the areas of common land in the south west. The last vestiges of these forgotten highways can still be found at the Fincham Nature Reserve where the truncated remains of the drove road to Downham Market now act as a magnet for wildlife. Along the top of the map shown can be seen South Lane a route that runs east / west to the south of the village. The lane survives as a public footpath today.

The commons shown on the map provided grazing for the villagers livestock and it was this together with the produce from the disparate strips of arable land that sustained the life of village in an almost entirely mixed farming community. To the west of the village the commons consisted of West Heath, Mannel Brook, Besenel and Awfield known as the Cow Pasture. It was this area that provided employment and refuge for some of the poorest in the community.

The following was written in 1921 by Rev J.F.Williams, 1878-1971, who was Rector of South Walsham and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquarians. He has much published material, especially concerning Norfolk. The source of this article may have been a newspaper of the time and investigations into its origin are on-going. The article refers to the Hare map above and the Field Book that went with it.

This article could now (2024) be entitled Fincham FOUR centuries ago!

FINCHAM THREE CENTURIES AGO

By Rev. J.F.Williams

A glimpse into the past is always interesting, and never more so when it has to do with our own neighbourhood. We all like to look back sometimes and picture to ourselves the surroundings with which we are so familiar as they used to be, and to conjure up some kind of vision of the folk who once lived in these parts, just as we do now , sometimes actually in the very same houses. Generally we have to rest content with mere imagination, but occasionally we have the luck to stumble across some faded though precious document which gives us just the information for which we are seeking.

Here is a case in point. In the church chest at Fincham there is preserved, along with the parish registers and other parochial documents, a thin manuscript book of quarto size bound in parchment. It contains some 50 closely written pages which at first sight seem singularly prosaic and unattractive; and yet by means of this book and a somewhat tattered and torn map which goes with it, it is possible to see Fincham as it was 285 years ago.

The book itself records a survey of the parish made at the instigation of the Lord of the Manor, Sir John Hare, of Stow, in the year 1636. On the twentieth March in that year certain tenants, whose names are given, seventeen in number, having been duly sworn at a Court of Survey, “did walke abroad with William Hayward, the Surveyor there appointed, and did shew him the utmost bounds of the toune,” and at the same time informed him as to the owners and occupiers of the various plots and parcels of land., all of which he duly “set doune in the book following.” Not a rood or an acre is missed, not a cottage or garden is overlooked, and in this survey practically every nook and cranny in Fincham lies before us just as it was in the 12th year of King Charles.

Turning first to the end of the book we find there is a summary of all the different parcels of land previously described, and from it we learn that the area of “the whole toune” then consisted of 3487 acres. Possibly the parish may have been curtailed since those days, or possibly our friend William Hayward the surveyor may have made an error in his reckoning, but the fact remains that the above total is no less than 514 acres more than the area as marked on our present day Ordnance map.

Of the 3,487 acres given, the arable land of the parish accounted for 1,747 acres, contained in four huge fields averaging well over 400 acres apiece and named respectively Eastfield, Southfield, Langholmefield and Northfield. The enclosed land of the parish consisted of 1,028 acres, including all the dwelling houses with their yards, gardens, and paddocks, while the commons and waste-land made up the rest. The largest of these commons, which naturally lay on the outskirts of the parish, was “the great Common called the Westheath and Besenell” which lay to the south-west and consisted of over 400 acres. Sir John Hare, as lord of the manor, owned 1,094 acres in the parish. His two chief tenants were Mr Drury and Mr Gibbons, both of them members of old Fincham families, who farmed nearly 1,200 acres between them. There were several other farms varying from 116 to 377 acres, while a stretch of rough land, lying in the south-east corner of the parish and known as the Loyes, was rented by Mr Richard Pretyman who, as he did not live in the parish, was probably merely a “sporting tenant.”

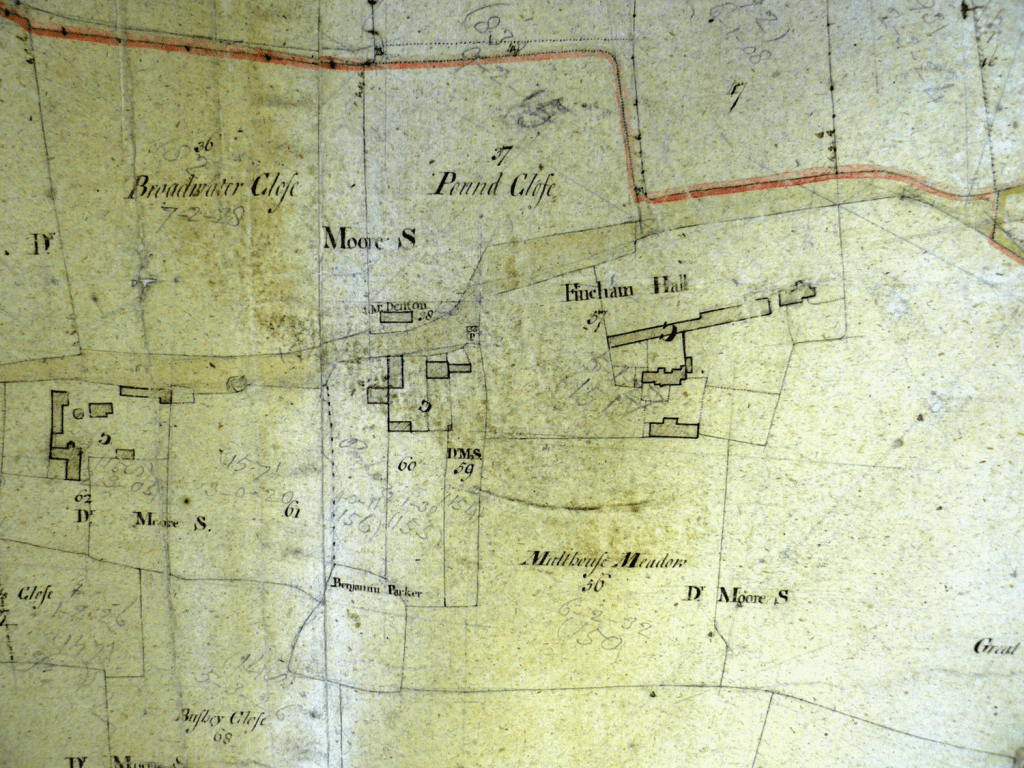

With regard to the roads of the parish some interesting variations may be noted. The main road ran through the village from east to west very much as it does now, but where it leaves the village to the east, near Fincham Hall, it divided into three parts, called respectively the Swaffham way, the Norwich way and the way leading to Broadwater and Boughton. The second of these seems to have followed the line of the present Swaffham road, “the Swaffham waye” inclining more to the north. Just at the fork of the Swaffham and Norwich roads stood that ancient institution the Pinfold or Pound, into which all straying animals were driven, only to be let out on payment of a fine to the “Pinder.”. At the west end of the village where the road to Shouldham Thorpe branches off to the north stood “the crosse,” presumably a stone wayside cross similar to those of stumps which still remain at Beachamwell, Langwade and elsewhere in the neighbourhood. Cutting across this main road at right angles, then as now, ran the road running northwards to Shouldham and Marham and southwards to Boughton. The northern part of this road is always known in our survey (in common with many other roads in this part of Norfolk) as “the Walsingham way.” In the middle ages the great Priory of Walsingham was undoubtedly the best known spot in Norfolk. Every year thousands of pilgrims from all parts of the country made their way to the famous shrine and it was only natural that a road leading in that direction should get to be known as the Walsingham Way. To the south the Boughton way followed the course of the present road, the only difference that in the southern part of the parish it ran over unenclosed land and not between hedges. These roads (except perhaps in the village itself) must not be thought of as wide metalled highways such as we have now, but as much more resembling the tracks which still run over our heaths and warrens today. Outside the villages there was very little wheeled traffic, and a track wide enough for a couple of horses to pass was generally sufficient. Goods were carried about mostly on pack-horses hence the fact that the smaller track leading from the Boughton way in the Stradsett road is known as the “the Packway.” The road leading to Shouldham Thorpe is Hungate, that is the “gate” or way leading to the meeting place of the Hundred which is known to have been situated somewhere in the northern part of Stradsett, or, as it is always spelt in our award, “Stredget.”

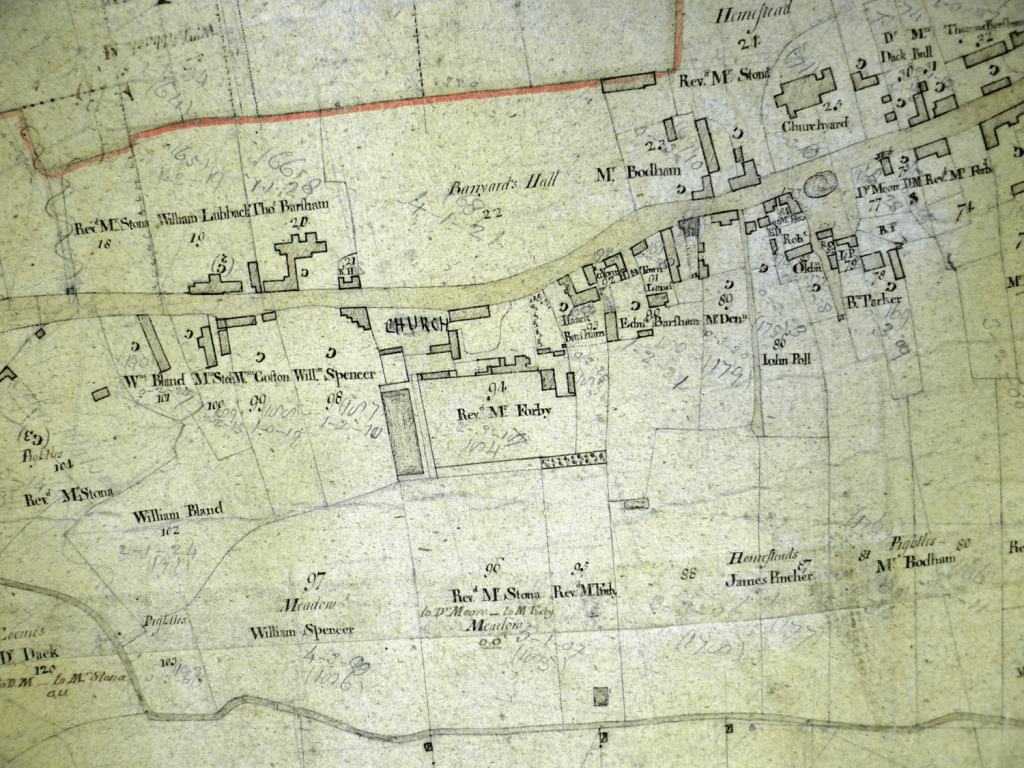

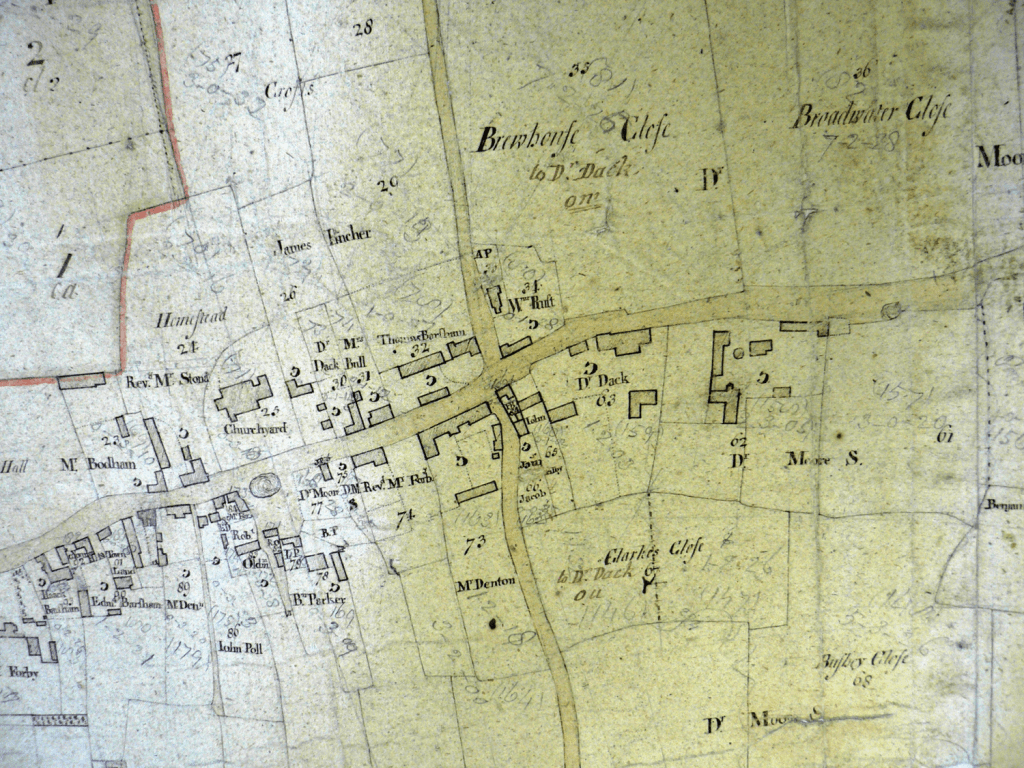

Starting now from the Pound at the east, let us make a journey through the village itself and see what changes have taken place since the year 1636. Immediately on the left of us lies the “site of ye manor of Fincham.” It is difficult from the minute sketch on the map to see what Fincham Hall looked like then, but immediately in front of the house stood a long low building probably a barn. A similar building, the malthouse, lay at the back of the house. Still further to the south was a narrow strip of water called “the mote” which connected up to the east with the “moteyard,” an oblong strip of land entirely surrounded by water. Near this, and overlooking a kind of tributary of this “mote” stood the “dovehouse” which, as was so often the case in an important manor seems to have been a stoutly built brick building. The “Elmeyard” and the “Oakyard” and “ye Lordes Close” all stood to the east of the house, while an orchard is marked on the west side. In 1636 the Manor House was in the occupation of Thomas Scott who, as we find from the parish register, had been churchwarden of St. Martin’s in 1628, 1629 and 1634. After passing Fincham Hall the road narrowed considerably, and there seems to have been some kind of gate across the road. On the south side of the road was “an old lane” called Walleswent Lane. It was “out of use” in 1636 and all traces of it have entirely disappeared. A little further on, a small pond, the outline of which may still be traced stood by the side of the road, and on the north side of the road more westwards was the “brewhouse” another appurtenance of the manor.

We now come to the cross roads. At the corner on the west side of the Boughton way, was a fair sized plot of ground occupied by Widow Howson and next to it is a narrower strip of land marked “the site of the vicarige of St. Martin’s, the house and croft.” Though the map fails to show any house standing on this plot it was undoubtedly here that the Vicar of St. Martin’s lived, the Rector of St. Michael’s living further down the road. The pond in front of St. Martin’s church was very much as it is now, though there was a small cottage almost adjoining it at the east end. The space immediately behind the pond is in 1636 recorded as “a pece of wast grounde belonging to the Chappell of All Saints.” but in an earlier survey of 1575 which Canon Blyth saw at Stow, this is still more fully specified as “waste ground called chapel hille, late All Saints” of which all all other record has now disappeared.

St. Martin’s church on the other side of the road probably looked very much as we see it now though since then the churchyard has been considerably enlarged. At the south west corner of the churchyard it is noted that “the toune hath a little house and a curtilage now used for a schoolhouse,” which shows us that education at Fincham s not entirely neglected in those days, though the accommodation in the “little house” must have been small.

Crossing the road again we come to another interesting site. Just to the east of the late Mrs Barsham’s house, a little way off the street stood the Gildhall, the meeting place of the various parish gilds or friendly societies. In the Public Records Office among the “gild certificates” are are returns from three Fincham gilds, dedicated respectively to the Assumption, St. Anthony and St. John the Baptist, all of which were in existence in the 14th century. In addition to this we have another reference to a gild at Fincham in the will of Simeon Bachecpost of Bexwell dated 1305 in which a bequest of 6s 8d was left to St. Martin’s gild of Fincham. We next come on the south side of the road to The Rectory of St. Michael’s, and to the west of it St. Michael’s church, which in 1636 was still standing and in use. It has now entirely disappeared and only isolated fragments scattered about in various corners of the parish remain to tell us something of its history. It was a smaller church than St. Martin’s, but judging from these fragments parts of it must have been of a somewhat earlier date. The church itself was pulled down in 1745 and the tower was removed some six years later. In front of the Rectory and adjoining the road was a long low building which very possibly may have been the tithe barn of the Rector of St. Michael’s. The Rector in 1636 was John Collin, M.A., who was instituted in 1617 and remained at Fincham for more than forty years. The Vicar of St. Martin’s was William Parker, M.A., who also continued in office for over forty years contemporaneously with Mr. Collin. He was instituted in 1615 and, as the parish register quaintly records it under the year 1657, “Master Willyeam Parker, vicar, was bured the twente one of october.”

Opposite the Rectory, “the site of the maner of Banyards hall” is marked though there are no signs of any buildings there. This was one of many small manors into which Fincham was divided and and derives its name from Sir Ralph Bainard, one of the conqueror’s knights to whom the manor was granted. Other sites of manor houses marked on the map or mentioned in the survey are Coombe’s manor on the left side as the road curves round to Stradsett; Little Well Hall on the same side almost opposite the chapel (and not on the site marked on the Ordnance map); Fairswell manor, on the left-side of the Boughton way where it began to cross the open pasture; and Curple’s manor, to the west of St. Michael’s church.

One other interesting fact must be mentioned. The Swan Inn in these days stands on the south side of the road somewhat further west than St. Martin’s church. But in 1636 “a tenement and yard called the Swan” (presumably an inn) stood on the opposite side of the road, apparently in the field between the Manor House and Mr Markham’s shop.

There are many other points of interest in this old 17th century survey worthy of a closer study but enough has been said to show how possible it is from such apparently uninviting material to draw a very fair and accurate picture of a Norfolk village as it was several hundred years ago.

************************************************************************************************************

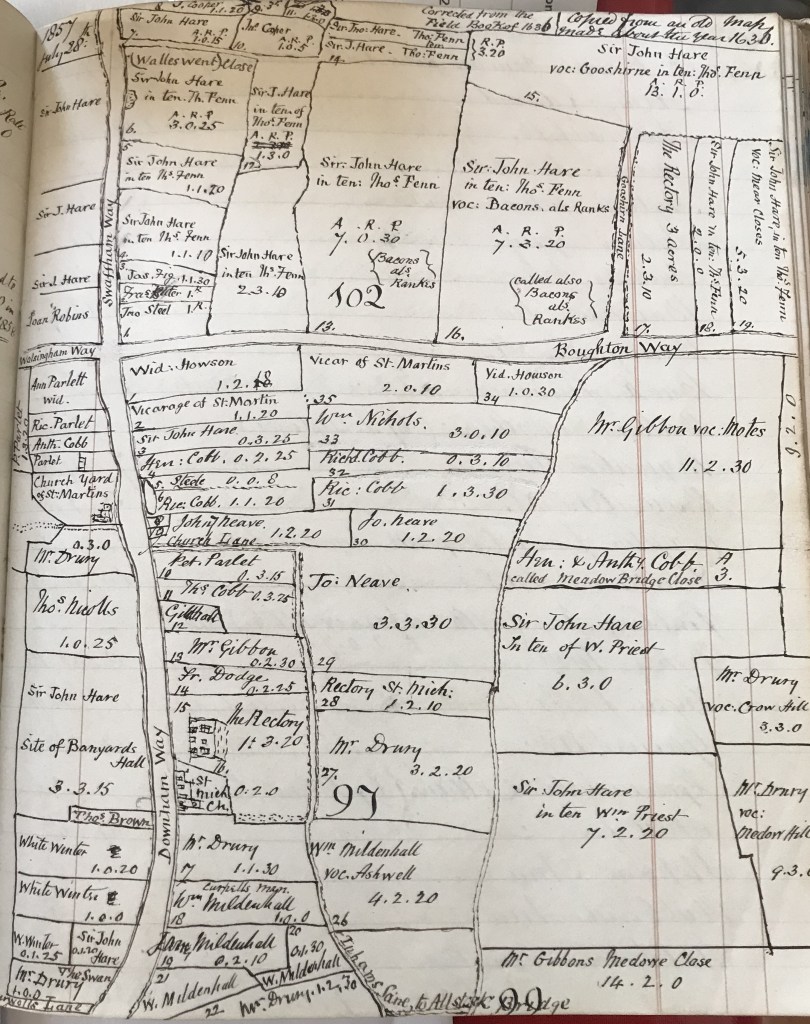

In 1853 William Blyth drew a copy of the central part of the Hare Map and added names from the 1636 Field Book.

Some of these names are Sir Thomas Hare, Sir John Hare, John Steele, widow Ann Parlett, widow Howson, Anthony Cobb, Mr Drury, Thomas Brown, White Winter, Peter Parlett, William Mildenhall, John Neave, Richard Cobb, Henry and Anthony Cobb, Mr Gibbon (Guybon), William Priest, William Nicholls, Thomas Nicholls.

Later in his Land Tax book he write:

By Deed of Release dated March 3 1655 Marmaduke Cobb son of Henry and grandson of John releases to John Cobb son of Anthony his uncle (brother to Henry) all his claims and rights in the Meadow Bridge Close (known as Marks Close by the 1850s) for the sum of £24. Witnesses Thomas Cobb and others

************************************************************************************************************

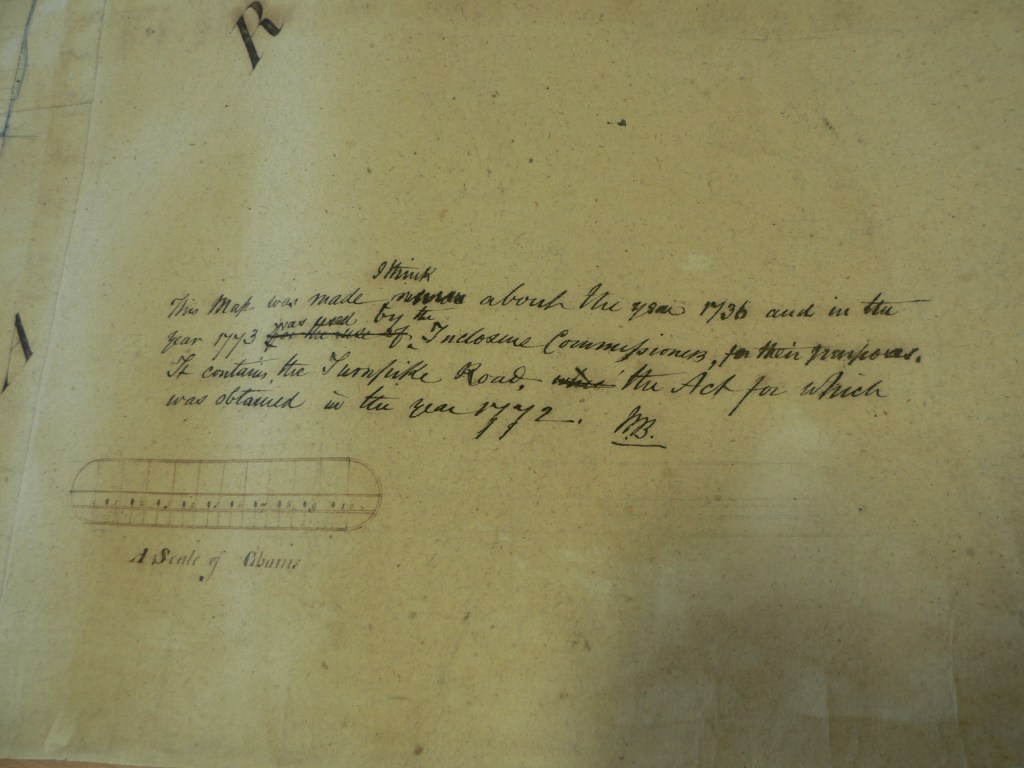

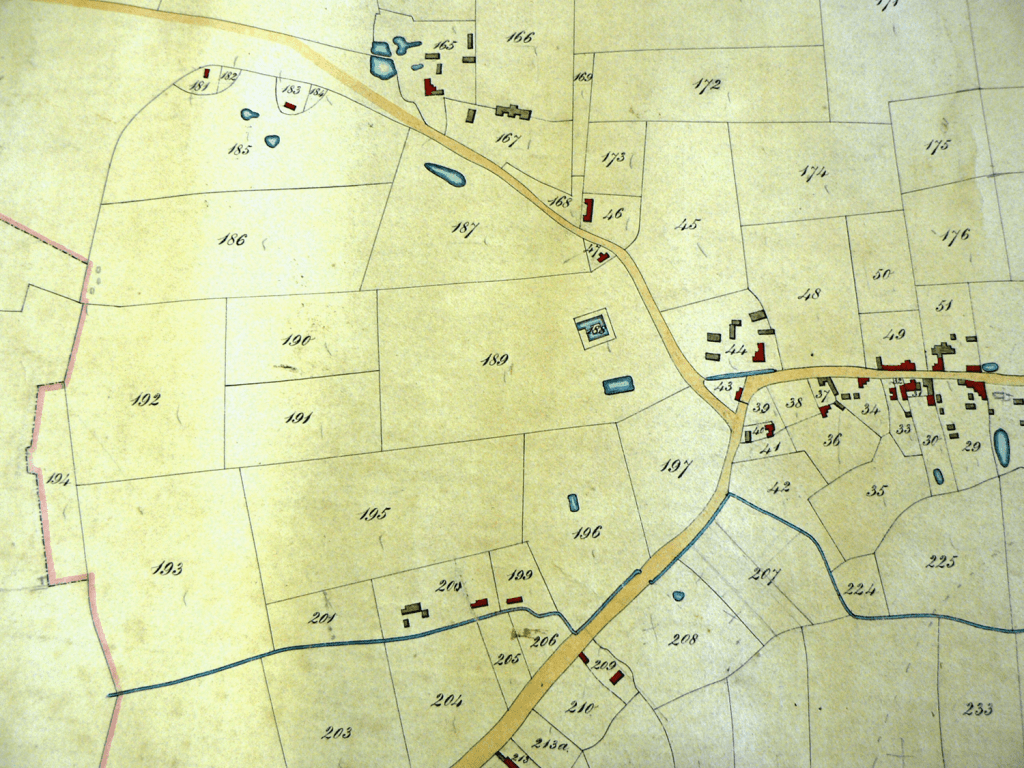

The 1772 Enclosure Map

Fincham was one of the first parishes in the region to enclose its commons and the Enclosure Map of 1772 gives us another snap shot of the village as it continued to grow throughout the 18th Century and the agricultural revolution that would follow enclosure. Certainly there were a number of large land holders but there were also many of the middling sort who gained from enclosure. The loss of common grazing rights may well have pushed those on the margins of the local economy into poverty and its effects would be seen in the take up of poor relief and the Work House in the years to come.

***********************************************************************************************************

Note on Enclosure Map made by William Blyth 1846-1886

************************************************************************************************************

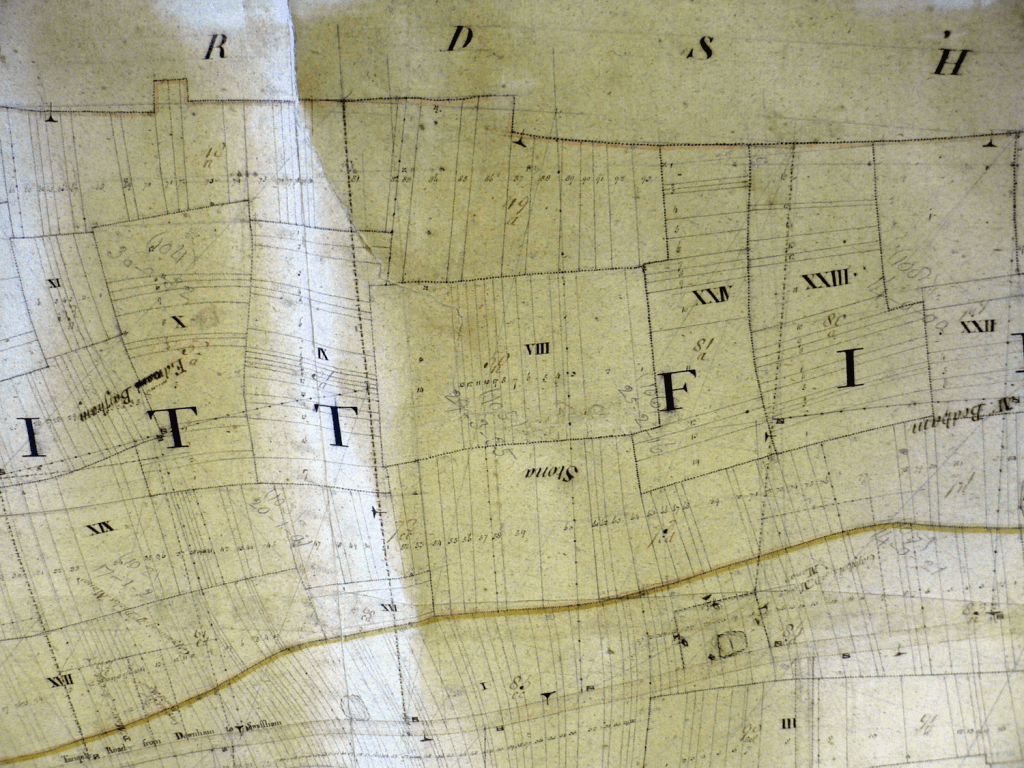

Extracts from the Fincham Enclosure Map of 1772 which is drawn on an older map of c.1730

The ancient system of dividing the land into strips, the large fields containing many of the strips and the commons can be seen from the old mapping. The new ‘enclosed’ field boundaries are superimposed over this old system. There are however many examples, especially near the village, of old enclosures.

************************************************************************************************************

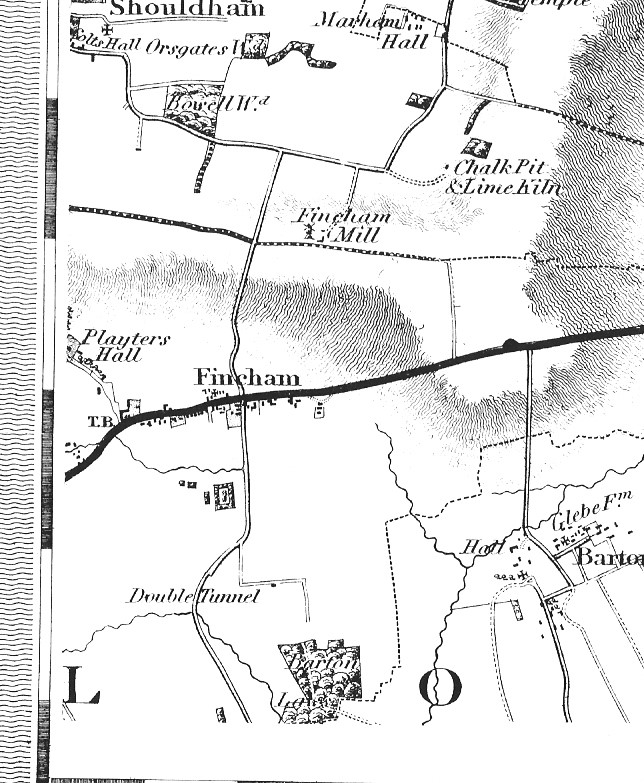

This map was published by William Faden, called ‘geographer to King George 111 and the Prince of Wales’. It is a scale of one inch to one mile. Parish boundaries are not shown but Hundreds are. Faden used a system of hachures to show relief. For example you can see the higher land as you go north up the Marham Road on which Fincham Mill is marked, The only house named is Playter’s Hall. The map was sold on a subscription basis and it has been suggested that subscribing to a map would have got your house named! Certainly the Finchams were long gone from the Hall but one would have expected it to be named. There is a farm marked where Raven’s Farm is today. There is a toll gate marked near Playter’s Hall on the way to Shouldham Thorpe -and hence Lynn. There was a cottage on this road within living memory, but now demolished, called Toll Cottage. Only a small area of trees is marked and no obvious commons -Fincham was already enclosed of course. Road layouts compared to existing roads are interesting to work out.

Andrew Bryant published this map in 1826. It shows parish boundaries, unlike Faden. It is on a scale of 10 miles to 12.25 inches which is about the same as the modern Landranger O.S. maps. You can see details of houses more clearly than on Faden’s map. A Toll Bar (TB) is shown near Talbot Manor across the Downham Road. The ‘Double Tunnel’ is puzzling. The Lode Dyke couldn’t have been much different from now and it is strange a tunnel is worthy of mention let alone a ‘Double Tunnel’. Fincham Hall is still not named but much clearer in detail. The large plots of Ivy House, the Rectory and Talbot Manor are shown, as is the moat that gave its name to the house soon to be built. A small area of Fincham is shown on the map to the west of this part. It has nothing on it except Black Drove is named.

************************************************************************************************************

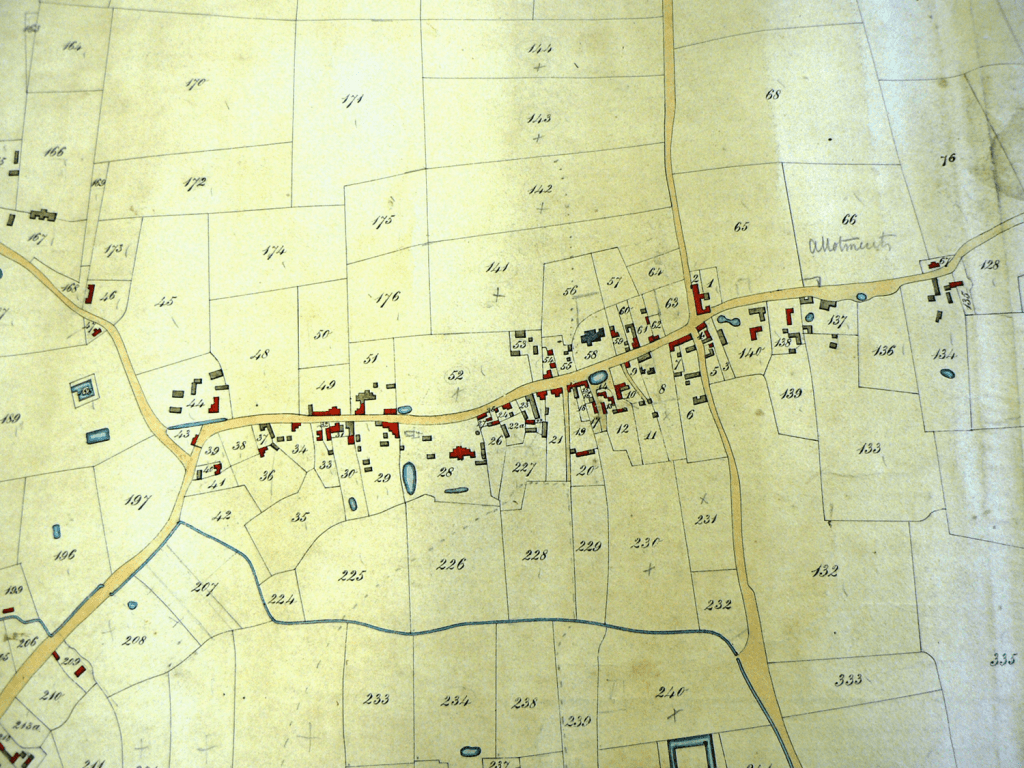

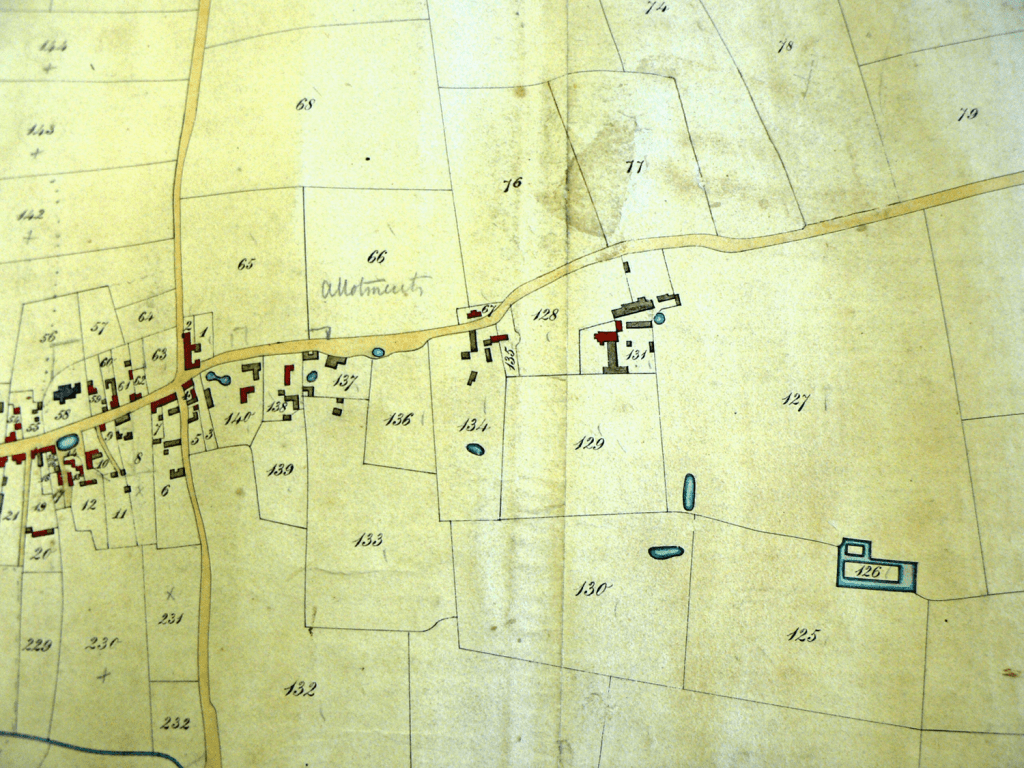

The 1839 Tithe Redemption Map

By the time of the 19th century, the whole system of paying tithes had become confused and was causing much resentment. Many tithes were being paid not to the church itself but to landowners who had taken over the tithes during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. The tithe system discouraged farming improvements. If the farmer grew more crops on his land he had to pay more of them as tithe. The Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, meant that each field or titheable plot had to be valued and the tithe map and its apportionment were drawn up for this purpose.

A tithe map was drawn up for almost all rural parishes in Norfolk between 1836 and 1850. This was necessary because the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 asked that payments of tithe in the form of farm produce should be replaced by a money payment. Tithe was a tax, which was paid to the local church.

Each map will show at least the boundaries of woods, fields, roads and waterways and the location of buildings. The houses are sometimes shown in enough detail to show their shape. Occupied structures are shown in red whilst support buildings such as sheds cart stores and barns are shown in black.

The Tithe Redemption map of 1839 shows the buildings, many of which still exist today. There are 69 occupied structures within the whole parish and when the census return of 1841 is examined then there is a strong indication of the sort of overcrowded conditions that must have existed for many in the village at this time. Furthermore, many of the cottages that are shown on the map were smaller than the structures we see today.

Houses are in red, outbuildings, barns etc dark