The history of the Fincham family that lived in Fincham is long and complicated and needs careful analysis . Fincham Hall was the family home for many centuries.

In the years leading up to his 1863 publication, the full title of which was ‘Historical Notices and Records of the Village and Parish of Fincham in the County of Norfolk’, Rev William Blyth had access to the archives in the Stow Bardolph estate of Sir Thomas Hare, Baronet, who was Lord of several ancient manors of Fincham and owned a considerable portion of the parish. It is worth quoting the first paragraph of Chapter XIV which is called ‘The Finchams of Fincham’.

The value of any statement that pretends to the importance of an historical record depend, of course, like other truth, on its authorities. These in the case of the Fincham family are unusually abundant and good. Very numerous Deeds of sale or gift etc., marriage settlements and wills, at Stow; together with Wills, Inquisitions, etc, at the public offices, have yielded a large amount of original and unquestionable evidence for our purpose. Anything herein that is not thus specifically authenticated is taken from the History of Norfolk, or other well known literary publications, Visitations of the Heralds, or genealogical MSS. in the British Museum or elsewhere.

To support this claim there is in his diary this entry:-

30/12/1857

At British Museum, in the magnificent Reading room, consulting Harleian MSS for Fincham’s Pedigree. Returned in time to join a party at Denver. Home by 11 o’clock.

N.B. The spellings Fyncham and Fincham seem quite interchangeable most of the time. For convenience the latter spelling has been mainly used.

There is no direct reference in the Domesday Book of one of William the Conqueror’s knights assuming the name Fincham after being given the manor. One Nigellus is named in Fincham but no connection with any other Fincham family is known. Blyth says, ‘Be that as it may, it appears certain, from the history of the Priory of Castle -Acre, that in the reign of William 2nd,(1087-1100) one ‘Nigellus de Fyncham’ gave his tithes to that monastery.

So, says Blyth, ‘From him, it has been assumed, descended the ancient family of Fincham, residing in this village for nearly 500 years and connected with some of the best families in the county,’ He however then says that early records bearing upon this point are so scanty and obscure, that it is impossible to settle this question with any degree of certainty.

One day, Blyth suggests, someone may ‘further search into the public records’ to get a true idea of the Fincham family history. The Hare family archives which would be a significant part of any research are in the Norfolk archive centre and await anyone interested in Fincham family pedigree. They are an extraordinarily vast collection -the index alone consists of many volumes -and it is unlikely anyone will have the motivation and access to the collection to try and work out the pedigree in the near future. The connection between the ancient family and modern Finchams has never been established in an unbroken line despite modern ancestry websites finding much new information.

So the way forward in this article is to list Fincham family members whose existence is fairly certain from the researches Blyth did, especially in the Hare archives,and who lived in Fincham. There is little point in detailing the extended family tree on this website. Anyone interested in the family trees that Rev William Blyth drew up should consult his book which is available on the internet.

****************************************************************************************

Nigellus de Fincham

From a history of the Priory of Castle Acre in the reign of William 2nd (1087-1100) Blyth found that one “Nigellus de Fyncham” gave his tithes to that monastery. (Dugdale, Monast. Angl. vol 1 p. 626 is Blyth’s reference). Although direct descendants haven’t been verified he must have been a landowner to pay tithes and must have lived in (or certainly had land in) Fincham.

Blomefield’s History of Norfolk and ‘Deeds at Stow’ are the sources of information for Blyth’s list of these next few Finchams but as previously noted he found no known connection to Nigellus.

Osbert de Fincham lived in the reign of Henry II (1154-89) His son and heir was Robert de Fincham whose son and heir was John de Fincham,the first of many Johns. His son and heir was Richard de Fincham mentioned in a document of 1259.His son an heir was Laurence de Fincham and his son and heir, Thomas de Fincham, is mentioned in a document of 1321. His son and heir William de Fincham is mentioned in a Deed of 1345.

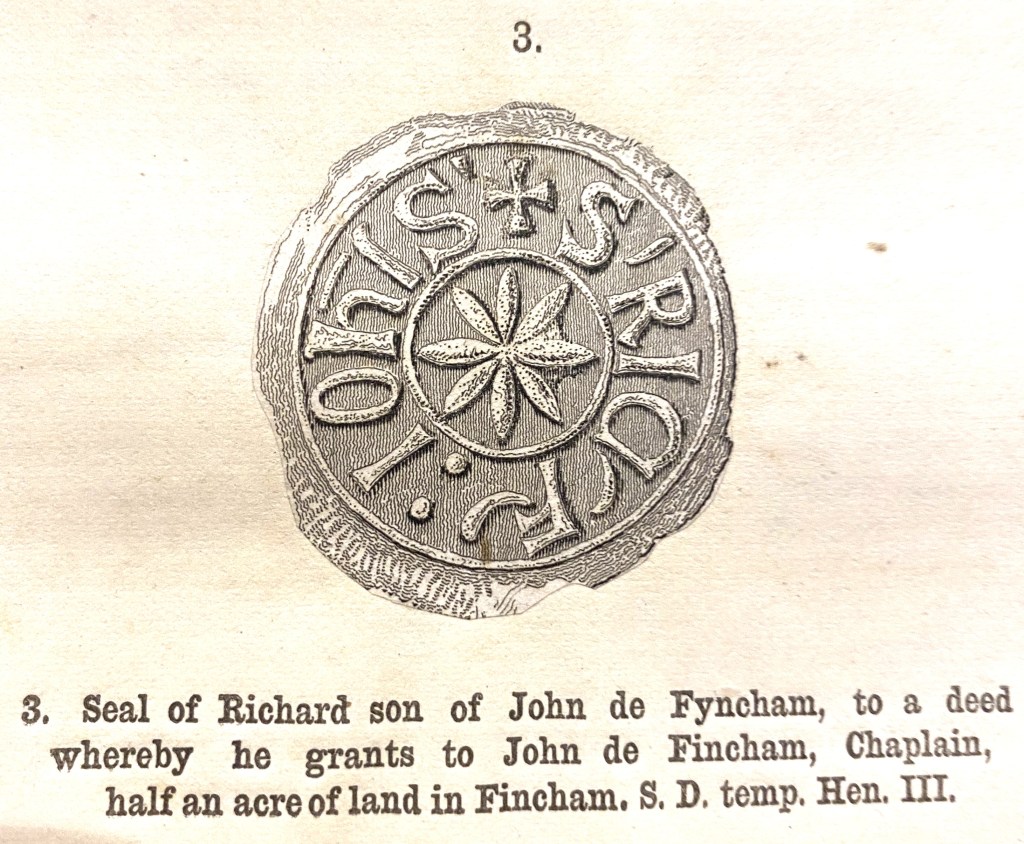

Seal of Richard in the reign of Henry 3rd 1216-1272 (from Blyth’s book)

****************************************************************************************

There is now a hiatus in the family tree. As Blyth says there were no less than thirteen manors or lordships in the village and and any of the lords might be styled ‘de Fyncham’. Blyth can find no connection between William de Fyncham and the next certain notable member of the family Adam de Fyncham.

****************************************************************************************

Adam de Fincham

Blyth calls Adam ‘the great man of the family’ and suggests – and really proves-that all subsequent members of the Fincham Hall family were descended from him. From Blomefield’s History and Wills, Deeds, Court Rolls and Registers he examined Blyth is reasonably certain of Adam’s pedigree and descendants. Adam was the son of Thomas de Fincham and his wife Cecilia. They were both living in 1296. Thomas is described in various Deeds as Pistor de Fyncham which means he was a baker. Although it doesn’t sound very impressive millers and bakers were very important people and had a good income. Anyway Adam was born about 1270. He rose to become Attorney General. The position of attorney general had existed since at least 1243, when records show a professional attorney was hired to represent the King’s interests in court. The list of Attorney Generals gives his dates as 1318-1320, 1324-1327 and 1327-28 (the last a joint position with another man, Alexander de Hadenham.} Thus they were at the end of the reign of Edward 2nd and the first year of Edward 3rd. In some early Deeds he is called “Attornatum Regis” and “Clericus Regis” (Blyth). His wife was Annabill, daughter of David Downe of Snettisham. Adam died in 1338 and is buried next to his wife in St. Martins church. His income from his position must have been considerable. Blyth examined Adam’s will in the ‘muniments room’ holding Stow archives and says the original is in Latin and ‘I can find nothing so old by half a century in any of the Registry offices at Norwich, or in the Perogative Court of Canterbury in London.’

In the will it says “My best horse to proceed my body at my burial, for the use of the Rector of the said church”. This horse was a gift to the priest-the ‘second best chattel’ at the time was apparently reserved for the church. Another bequest was ‘To Robert the parish clerk of St. Michael’s my summer cloak with its hood’. And-‘A certain gold ring with which Annabilla my wife and I were united in marriage, and a certain gold brooch to be taken to the tomb of St. Edmund king and martyr [at Bury] and there fixed.’

Adam must have lived in a substantial house, perhaps not yet called Fincham Hall but certainly a house worthy of the name Manor House. Blyth avers that ‘there doubtless existed from the earliest times after the Norman Invasion a suitable residence for the lord of the principal manor in Fincham….. and it was no doubt of a superior character to the houses of the other manors’. Adam was succeeded by his son John.

****************************************************************************************

John de Fincham

Blyth could not find a will for John in the Stow archives but he did find ‘a very interesting Inventory of the goods and chattels of John, son of Adam de Fyncham, taken A.D. 1340’. This details the rooms in his house and mentioned are :-the chapel, the hall, the lord’s chamber, the spence or steward’s room, the kitchen, the bake-house, and the larder, besides out houses and farm buildings. Blyth says the present mansion cannot possibly have stood from that time and is a rebuilding on an old site. Although Blyth doesn’t specifically say so it is almost certainly the site of John’s house as it is difficult to see where an alternative site would have been.

Here is a copy of Blyth’s translation from the Latin of the original.

Innventory of the goods and chattels of John de Fyncham made on Wednesday the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel, in the 13th year of the reign of King Edward the Third after the conquest, at Fyncham, Barton and Thorpe. And the said goods etc. were delivered to Thomas Lay, his servant to be responsible for the same.

THE STOCK

2 young cart oxen

1 riding horse for the servant

2 young plough oxen

6 draft oxen

7 cows. Of which two are milch, four are dry

and one has been sent to the farm

7 steers 9 heifers

7 calves 2 sows 1 boar

7 pigs for killing

20 little pigs

3 score sheep delivered to Henry Atland by a tally

30 goslings 18 fowls

12 hens 2 cocks

20 ducks and drakes young and old.

IN THE CARTSHED

3 iron-bound carts, with their coverings and ladders

2 ploughs with gear complete

2 harrows 1 barrow

IN THE STABLE

Complete harness for six horses to three carts, but some of them want mending.

1 pair of odd traces for the cart.

3 cart ropes. 3 binding ropes.

1 spade 2 suffle bags.

3 forks for manure

1 seed basket. 1 horse-skep.

IN THE BARN

3 long ladders for the stacks.

3 forks for sheaves. 2 riddles.

IN THE BAKE-HOUSE

4 coolers of metal.

4 coolers of wood.

13 vats and tubs. 3 soes

2 metal boilers in the furnace

1 leaden tap-trough

2 pails 1 iron-bound bucket

IN THE GRANARY

10 sacks 2 winnowing cloths

2 sieves. 3 portable chaff-baskets.

1 wooden bushel. 4 corn fans.

1 bin-basket. 1 fan for malt.

IN THE KITCHEN

6 brass dishes of which one is at Barton.

6 brass pots of which one is at Thorpe.

3 little pots. 1 chafing dish.

2 three-legged stools. 2 mortars

1 iron frying pan.

1 grate. 1 griddle, or grid-iron.

1 great knife for dressing.

1 hatchet. 1 iron-bound bucket.

1 brass mortar with an iron pestle.

IN THE CHAPEL

1 cup. 1 missal.

1 antiphoner. 1 gradual.

2 vestements. 4 napkins for the altar.

2 toncinells. 1 cope.

1 chesibule. 2 psalters.

IN THE HALL

1 hanging. 6 arrows (for the cross-bow).

4 tables. 1 sleeping bench.

2 pair of trestles. 3 washing basins.

6 ewers. 4 hearth -irons.

1 iron fie-cover. 2 pair of tongs.

3 chairs.

IN THE PANTRY

16 silver spoons.

3 pieces of plate, of which one has a silver lid.

1 cup of silver, which moreover is gilt.

2 maple bowls. 23 pewter plates.

24 dishes of the same. 24 soup plates of the same.

2 pewter large dishes. 2 salt cellars.

6 napkins. 7 table cloths.

12 towels. 3 canvas cloths for the hall.

4 barrels. 1 bread chest.

4 knives in a box for the lord’s table.

IN THE LORD’S CHAMBER

11 pieces of tapestry. 7 coverlets for the hangings.

27 sheets. 2 feather beds.

6 canvas cloths. 3 quilts.

2 bolsters. 5 pillows.

3 hacquetons. 2 bascinets.

1 hauberk. 5 spears.

3 cloaks. 4 chests.

3 packing chests. 4 little boxes.

3 cabinets. 2 battle-axes.

1 striped mantle or rug.

IN THE LARDER

1 chest for meat.

1 small meat pot.

2 upright salt barrels.

1 skimmer of bass. 2 weights.

1 hammer. 1 pair of pincers.

1 cleaver. 1 long knife.

1 bow. 33 arrows.

Blyth’s glossary of unusual words.

Suffle bags -saddle bags soes -large tubs with two ears carried on a pole. antiphoner – choral service book gradual-another service book tonicells-a robe for the sub-deacon cope-another robe chesibule-a short robe for the priest hacquetons– quilted jackets worn under the armour bascinets -helmet caps

This inventory dates from 1339 and reflects the significant status of the family in the middle of the fourteenth century, much of it surely due to the high office that Adam achieved. The Lord’s chamber and hall must have been sizeable rooms. The kitchen, pantry and larder show a great range of domestic items. There is no illustration known of this hall but the inventory gives us a glimpse of what life must have been like for its owners.

John married firstly Alice, daughter and heiress of Robert de Cawston in about 1347. Their eldest son and heir was another John. A second son, Thomas, was given by his brother, in about 1400, the Manor of West Winch which Blyth says (1863) is now called Fincham’s Manor. A daughter Alicia, married Laurence Trusbutt of Shouldham. John married secondly Christiana Chappe or Chapps from Wolverton. Their son Edmund Fincham started a branch who lived for many generations in Rougham. John died between 1371 and 1374 and is assummed to be buried next to Alice in St. Martin’s church (Blyth)

John de Fincham

This John married a Katherine from Briston (father’s name not known). John’s seal was a shield containing three finches. He and Katherine had seven children recorded by Blyth, the eldest Simon being the heir. John was buried with his wife in St. Martin’s church. The last Testament (Will) of John is dated in October 1415 and proved on October 15th of that year. From it we know he was buried in St. Martin’s. He left ‘ten pounds of silver’ to the church of St. Martin in Fincham and ‘forty shillings of silver’ to the church of St. Michael. This gift to St. Martin’s was huge and must have enabled the start of the church rebuilding in the 1420’s and ensuing decades.

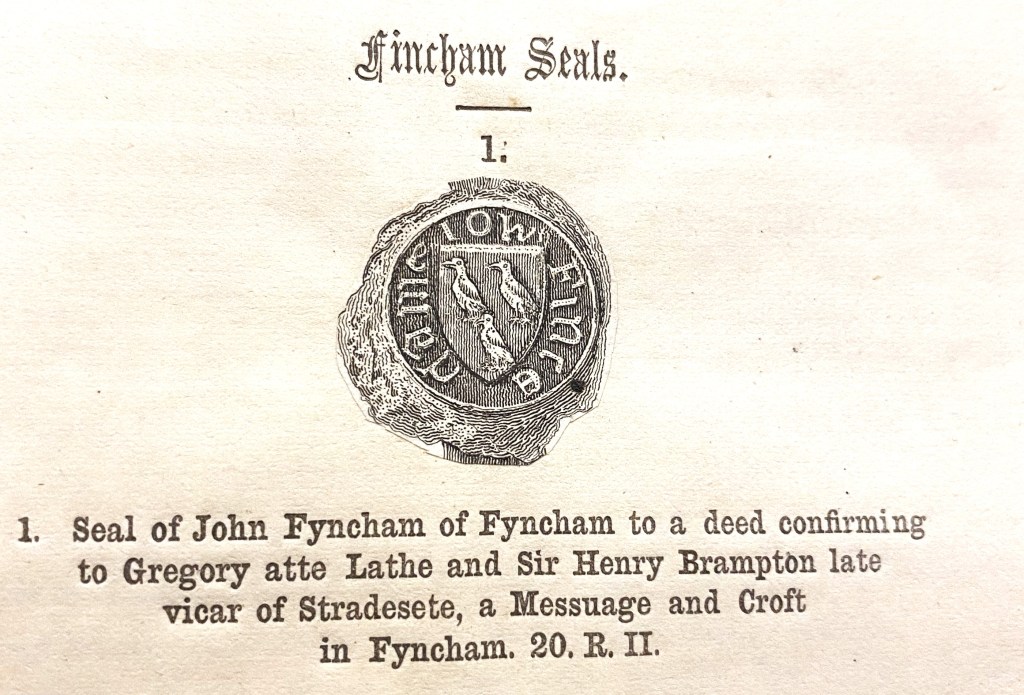

Seal of John Fincham in 1397 (From Blyth’s book)

So there is now a Fincham dynasty in a Hall in Fincham and increasing their wealth by judicious marriages and acquisition of more and more land. The next heir was John’s son Simon.

****************************************************************************************

Simon de Fincham

According to Blyth, Simon was listed in ‘Fuller’s Worthies‘, a book of ‘gentry of the county‘ as returned by the King’s Commissioners in 1433. He married Elizabeth, one of the co-heiresses of John Tendring of Brockdish. Blyth says that ‘to Simon we are indebted for the fine tower of our church.’ He was buried in St.Martin’s in 1458, and his wife Elizabeth in 1464. They had six children according to Blyth and two of their sons are significant in Fincham history. John was the heir. The fourth son was Nicholas who was ‘in holy orders’ and who built the Vestry of St.Martin’s church and is buried there. In Nicholas’ Will of 1503 he says: ‘ My body to be buried in the vestry of St. Martin’s church etc. I will that my executors perform and finish up the vestry that I have begun as far as my goods will extend, as I have showed unto them by my mouth in the past’. Blyth notes the vestry was built, like the rest of the church on ‘older work’, He says it formerly had an upper room in which a school was kept but from what date is so far unknown. John the eldest was the next head of the family.

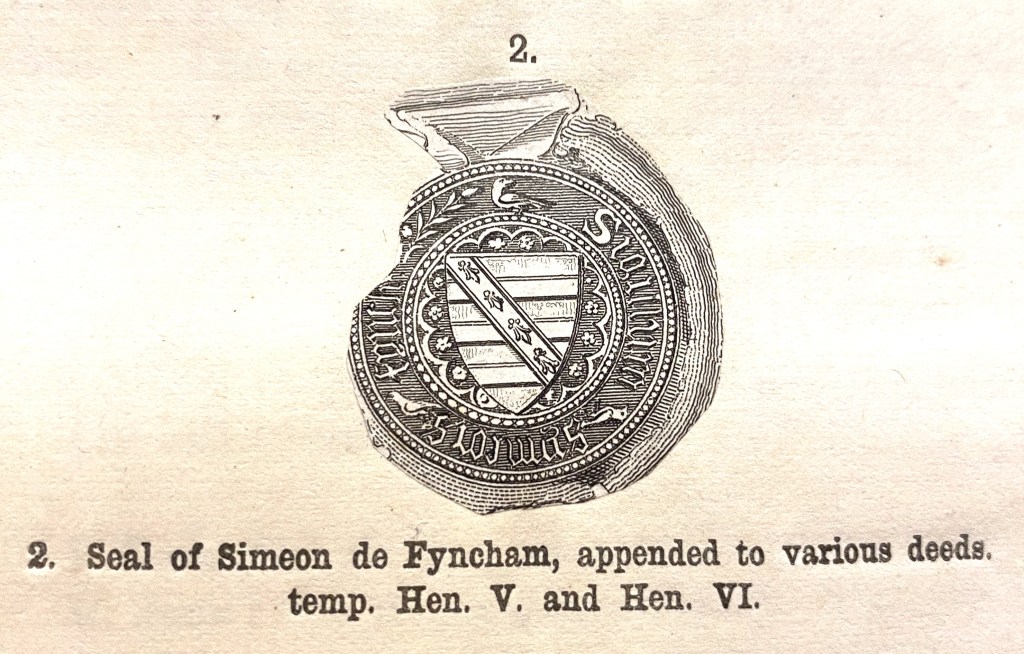

The seal of Simon showing the three finches separating the words SIGILLUM SYMEONIS FYNCH (AM). (The seal of Simon Fyncham) Time of Henry 5th 1413-1422 and Henry 6th 1422-1471 (From Blyth’s book)

The buttress of the tower of St. Martin’s showing the Fincham coat of arms -fourth from the top.

Simon’s will is written in English and is dated 1452. Blyth recorded it at Stow.

This is the last Will of me Simon Fyncham of Fyncham in the county of Norfolk, Gentleman. Firstly I will that all my estates in my use in all my lands and tenements in the said County after my death and of Elizabeth my wife go to John my son and to his heirs…..

After this there is a lengthy list of second, third and other sons and nephews and their male progeny who may inherit his estates if others are ‘without issue male’. If all sons die wihout issue then ‘after the female issue paid and content ,(my executors) shall sell all the said lands etc. and the money made therefore be be disposed for the souls of me and my wife and our said issue,and of all our ancestors and friends, in such ways as can be thought of to their discretion, the said souls long to be held in prayer and remembrance.’ 10th October 1452. ***************************************************************************************

Here is an extract from an article that is largely about Nicholas Fincham, Simon’sbrother, who founded the vestry.

THE PLACE OF THE ORGAN IN THE MEDIEVAL PARISH CHURCH

An article written for the 37th journal of the British Institute of Organ Studies, 2013

Nicholas Fincham 1505

Dashwood, G.H., ‘Wills at Stoke Bardolph, from Muniment Room there’, Norfolk Archaeology , Vol. 2 (1849). (Martin Renshaw’s modernisation: )‘ My body is to be buried in the vestry of St Martin’s church in Fincham. I will that my executors carry on with and finish the vestry I have started, as far as my assets allow, in the manner that I have previously explained verbally to them. The churchwardens are to use the rents and profits of the land I have given to the church for the following provision, that is to say that the said church wardens in office at the time, taking into account the opinion and agreement of the person or persons who are the rightful heirs of Fincham Manor in Fincham, shall hire on an annual basis a suitable and appropriately-trained clerk to serve at and assist in holy worship in the said church of St Martin at Fincham, and to play the organ, and to teach children so that God’s worship may be improved and supported, and they are to pay him a mark [13s 4d] every year from the said rents and profits, to be paid four times a year, that is 40d [3s 4d] a quarter, and that the said mark will not be deducted from his pay for work he does for the parish … And if it so happens that any ‘curate’ does not keep up divine worship because he does not know how to sing, or for any other misdemeanour, so that the holy worship of God is not improved and supported, but diminished and damaged by the curate, then the said mark to be given to the poor yearly on Good Friday, as long as they shall be without a suitable and trained cleric to have and to do this job …

The case of Fincham in Norfolk, where it seems that a local manorial family (the Finchams) not only supported the church but produced some of its priests as well – perhaps trained through the monastic or collegiate system – can perhaps be paralleled, though on a larger scale, with Etchingham in Sussex and Lingfield in Surrey. In both of these places local sub-aristocratic families built and endowed what were essentially private chantry colleges in churches which were only partially parochial as well. (I am indebted to Nigel Saul for pointing me towards Etchingham and for showing me forthcoming work on the buildings of Lingfield College.) Martin Renshaw

****************************************************************************************

John Fincham

The ‘de’ has now been dropped. John married Beatrix the daughter of Henry Thoresby, a wealthy King’s Lynn merchant in about 1446. John was ‘steward of the manors of the Abbot of Ramsey, who was Lord of the Hundred of Clackclose.’ Fincham of course is in the Clackclose hundred. No doubt the position was very remunerative. Now, importantly, Blyth speculates that Fincham Hall was probably built by this John Fyncham. The polygonal tower that remains is considered to be late fifteenth century and dates from about the same time that similar towers were used for Oxburgh Hall gatehouse. Blyth discoverd the strange fact that John and Beatrix had two sons named John. apparently alive at the same time! The younger John became the founder of the Fincham dynasty at Outwell. The elder John is said (Blyth) to have purchased the manor of Burnham Deepdale in 1474. John the father died in 1496 and was buried with Beatrix in St.Martin’s church. He was succeeded by his eldest son John, called the ‘elder John.’

Imagine the Hall with a second octagonal tower matching the one on the left.

John’s Will is dated March 10th 1494 and so long Blyth didn’t copy it all out because, he says, ‘of the high charges of copying wills at the ‘Doctors’ Commons.’ After saying that his debts should be settled out of his estates, and income from his estates at Brancaster and Deepdale should not included, he says his executors should ‘ find and sustain an honest and well disposed priest secular, that shall yearly and daily, if sickness and other reasonable causes let him not, to sing or to say mass, and all other divine service relating to an annual priest.’ An annual was a priest appointed to say mass for one whole year for a deceased person. His will continues ‘and in his mass to remember and pray for the souls of me and Beatrice late my wife, and the souls of my father Symon Fyncham and Elizabeth his wife, my mother, and for all my good benefactors and good doers in general etc. Which priest to say the said mass I assign my brother Sir Nicholas Fyncham if it may please him to take it upon himself, before any other priest, taking yearly for his salary six marks and his board, so that he be content to go to board with my son the elder John, as he has done so for this time,’ There is more on Sir Nicholas.‘and the said Sir Nicholas shall have the said service and chantry if it may please him during his life and shall sing and say his mass etc.in the parish church of Saint Martin, or in the chapel of our Lady within my Maner (=Manor House) of Fyncham.’ There is more on continuing with a priest if Sir Nicholas is unable to carry on due to illness or if he refuses to do the duties. If a priest is not ‘of good conversation and disposition’ he authorises them to be ‘put out’ by his heirs.

The Fincham’s were now a significant family.They had a large newly enlarged house with its own chapel and estates in Fincham and other parts of Norfolk.

***************************************************************************************’

John Fincham

This John was 44 when his father died in 1496. He died soon after in 1499 and is buried in St. Martin’s with his second wife Jane, daughter of John Tey, an Essex man. John’s first marriage was to Alice, daughter of Thomas Bedingfeld of Oxburgh Hall in 1469 and Blyth could find no trace of children. Alice is buried in Merton near to her sister Mary, wife of William de Gray of the Walsingham family. With Jane he had three children at least, the eldest being another John. His will leaves to his wife,Jane, ‘all my manors, lands etc. within the town of Fyncham’ and ‘manors and lands in Hunworth, Stody, Barton etc.’ His executors ‘shall take all issues and profits of my manor in Deepdale, with 600 sheep there left for store etc. for the marriage of my daughter Margaret, and after that performed then I will that my son, John, have the said manor of Deepdale to have and to hold to him and his heirs for evermore.‘

****************************************************************************************

On the floor of the aisle in the chancel of St.Martin’s there are several large black purbeck marble slabs dedicated to members of the Fincham family who were buried in the church. The brasses that were attached to the slabs were removed -one can only assume stolen- centuries ago.

This one is almost certainly that to John de Fincham who died in 1499. He is presumably the figure in the middle and his two wives, Alice (Bedingfield) and Jane (Tey) on his sides. A man named John Weever published a book (Funeral Monuments) in 1630 in which he recorded the inscriptions on three brasses which were later taken or stolen. One said:-

Pray for the soul of John : son and heir of John Fyncham son of Simon Fyncham who died last day of April 1499

The other two inscriptions relate to the other two indents.

pray for the soul of Elizabeth, the late wife of Simon Fyncham, Armiger, and of one of the daughters and heirs of John Tendring of Brockdysh in the county of Suffolk: Armig: Elizabeth died in 1464

pray for the soul of John Fincham son and heir of Simon Fincham of Fincham who died 6th September 1496

This is the sole surviving brass from the sixteenth century which could be a member of the Fincham family-it is called a lady in a shroud.

****************************************************************************************

John Fincham

This John married Ella (Eyle in Fincham register) daughter of Gregory Adgore, or Edgar,a Suffolk man, in 1519. Their first child was a boy whom they named John. Blyth thinks he died young before his father. He is not mentioned in his father’s will. His second son,Thomas, therefore became the heir. John died in 1542 and his wife Ella just two months later. In her will she bequeaths to Thomas ‘all my goods and weapons meant for the wars, and also ‘twenty shillings for mending the highways of Fincham, eight pence to every householder in the town’ and to Thomas ‘three rings of gold – marriage ring, husbands signet ring and one with a diamond and two letters.’ John’s will is worth quoting at length because of the detail of early sixteenth century Fincham it gives. The will is dated 1540 and John died at Norwich Castle on September 19th 1542. He was thus Lord of the manor of Fincham for forty two years, a large part in the reign of Henry VIII. His will, of course, is made at about the time of the Reformation.

‘first I commend my soul etc. -and my body to be buried in the church of Saint Martin on the south side of my father, and I give and bequeath to the vicar of the same church in recompense for my tithes negligently forgotten 6s 8d-and for the repair of the same church of St. Martin £3-6s-8d – also to the parson of St. Michael’s 6s 8d- and to the repair of the same church of St. Michael 40 shillings. To every parson or vicar of all such towns wherein I have land for tithes forgotten 12 pence. I will that my most eternally beloved wife Ela shall have the keeping, using and occupation of all my chapel goods as well as chalices, books, vestements etc. during her life , and after her decease then my son Thomas. I will that my said wife shall find an honest priest to say mass and pray devoutedly for my soul and all my ancestor’s souls according to the will of John Fyncham my grand father. I give to my brother (in-law) Skipworth my best gown and my best doublet: and I give to Ela Skipworth his daughter all such money as he owes me which is about 40 shillings. I will that my executors shall pay to my sister Skipworth for seven years and twice in the year at Michelmass and Easter, at each one 10 shillings. I give to one of my god children being a gentleman’s child 6s 8d and to each one of my other god children except John Copsey 20 pence, and to John Copsey 3s 4d. To my cousin Fyncham of Westwynch my black chamlett fur gown and to my cousin Thomas Fyncham of Well my black fur gown with coney. I give to Sir John my priest 6s 8d. To Thomas Complyn my servant £3 which I lent him. To John Bacon my servant 40s. To Richard Bacon 20s. To William Parker 6s 8d. To Ann Calybutt and Thomasyn Fyncham, being now childeren within my house, to each of them 6s 8d. To To every one of my women servants one quarter wages. I give to my wife all my goods, chattels, plate, money, debts, corn etc. on this condition- that she pay my debts, restore my wrongs etc. and deliver to Thomas my son seven hundred good ewes when he comes to his age of 21 years, and also ten cows and a bull. And I will that she shall pay unto Ela my daughter two hundred marks of good and lawful money of England when she shall come to the age of 21 years, in full recompense for all such sheep as I have given her before this day etc. and if my children die before the age of 21 years, then I will that my wife have the said bequest to this intent, to bestow it in deeds of charity amongst my kynsfolk and servants and poor folk, to pray for our souls and benefactors by her discretion. I give to Ela my wife all my lands and pastures in Bowton etc. Also where before this time by my deed I have granted to Ela my daughter an annual rent of 20 pounds. Also I will that my wife have two parts of the manor of Baynard hall in Fyncham in three parts divided, that is to say the site or mansion of the said manor, 40 acres in Southowe, a close in North field, a freedom to foldcourse for 40 sheep etc. All the residue of all my goods, chattels etc.I give to Ela my wife whom I make and ordain my sole executrix etc. and Sir John Spelman Kt superviser etc. Witness William Skipwith and others.

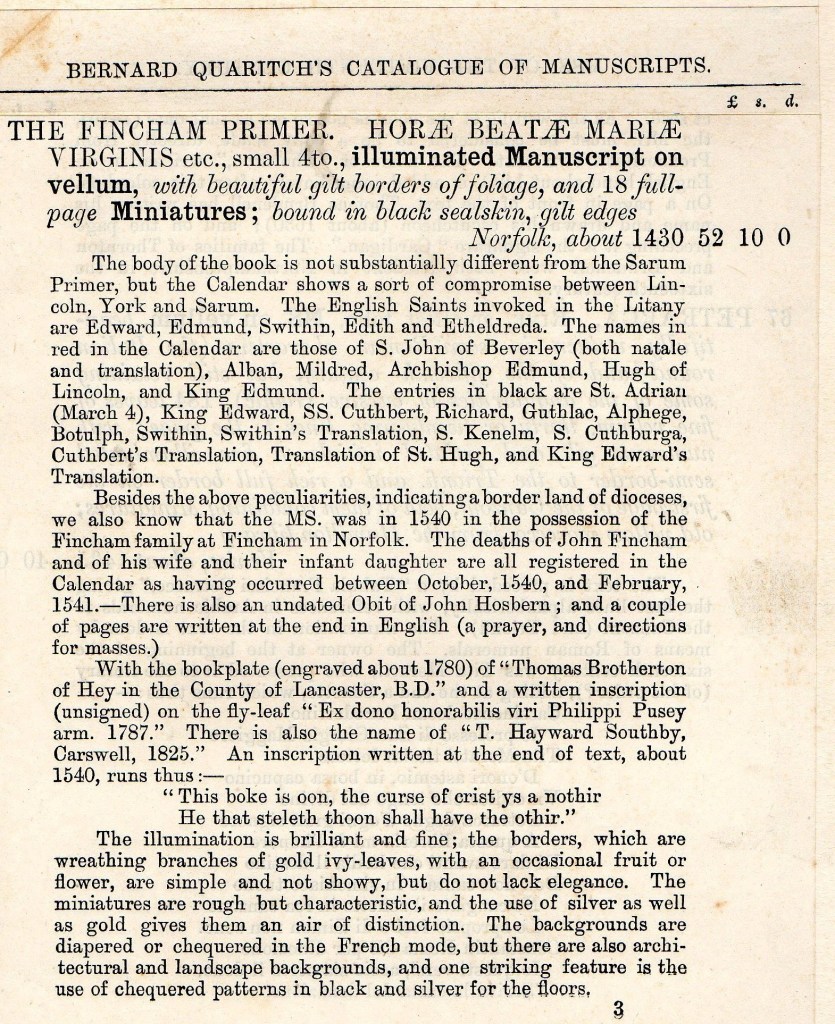

The following records that the manuscript known as the Fincham Primer was in the possession of the Fincham family in 1540. The deaths of John and Ela and an infant daughter are said to have occurred between October 1540 and February 1541. The infant daughter must have been born to Ela when she was aged about forty. This entry doesn’t say anything new anything about John and Ela but it is link to them as real people.

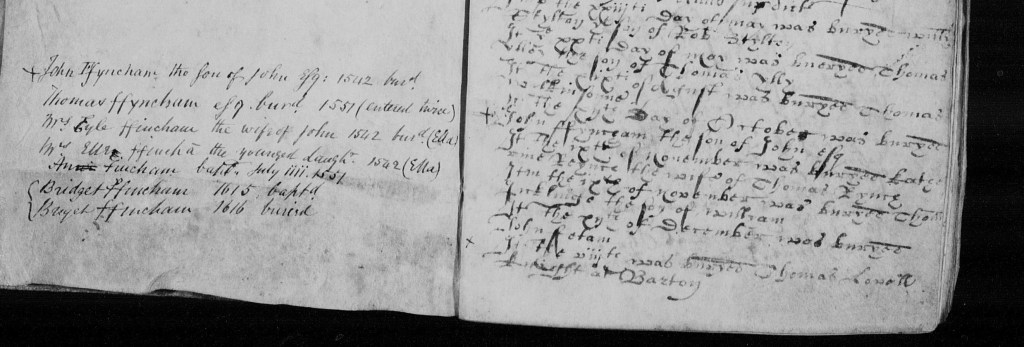

Extract from a Fincham Register which probably shows the correct dates of the deaths of John, Ela and their daughter

At some time in the early 17th century someone, presumably the Vicar of St. Martin’s, has summarised the entries for some Fincham family members. It is on a spare page of entries for 1542. It says:- (take your pick of spellings of ‘Fincham’)

John Ffyncham the son of John Esq 1542 buried

Thomas ffyncham Esq buried 1551 (entered twice)

Mrs Eyle ffincham the wife of John 1542 buried (Ella)

Miss Ella ffincham the youngest daughter 1542 (Ella)

Anne fincham baptised July iiii 1551

Bridget ffincham 1615 baptised

Bridget ffincham 1616 buried

Poor Bridget -she didn’t live long and we don’t know what her family line is. The handwriting as shown on the right hand side of original 1540’s entries is not too clear and spelling mistakes are easily made! ‘Eyle’ is almost certainly ‘Ella’ or possibly ‘Ela’. ‘Anne’ could be ‘Ann’ as it has been partly crossed out.

****************************************************************************************

Thomas Fincham

Thomas was the second son and heir to John and Ela and was a minor aged 12 years at his parents’ death in 1540-41. A Deed of Henry VIII in 1541 makes him a King’s ward. He died on July 30th 1551. He was only 23 years old and was buried in St. Martin’s church. It was Thomas who is the member of the Fincham family who was the head of the family during Kett’s rebellion. The rebels in Fincham are said to have told Thomas that they would ‘make a carte wey between his hed and shulders’ if he did not at once join them.’ This story comes from a nineteenth century book about the rebellion which quotes from a book about the rebellion written in about 1570 by Nicholas Sotherton and which includes eye-witness accounts. A longer quote is:-

The same year certain persons at Fincham were anxious to raise

the commons by ringing the bells in every town. One of them,

Thomas Stylton, was accused of saying, ” It were a good dede that

the Comynalte shuld ryse here as they cled ther ; for they ded ryse

for the Common Welth, and yf yee had ben ther as I was,” i. e. in

Yorkshire, where he had served as a soldier, ” ye shuld have hard

that they rose for the Wele of the Comynalte.” Their wish was that

Mr. Fincham, of Fincham, should join them, and if he would not,

“they would make a Carte wey betwext his hed and hys shulders;”

and next, that ” the halydays that wer putte down, shuld ” be

” restoryd ageyn,” which, they believed, would have been the case, if

the Yorkshire rising had succeeded, as they wished it had done.

With regard to this restoration of the holidays, it is only right to

state that, though the men of Fincham were desirous of retaining

them, others were of a different opinion, as appears from a ” Petition

to the King in Parliament,”

Thomas would have only been about 20 years old. There appears to be no record of his response to this threat (although he survived it!) or whether Thomas Stylton was one of the 300 rebels executed with Kett. Thomas Fincham married Martha, daughter of William Yelverton of Rougham. They had two children. William was his son and heir. Ann their daughter, was baptised on July 4th 1551 the same month as her father died. She married firstly Richard Nicholl, of Islington Norfolk. Secondly she married Charles Cornwallis, of Beeston, Norfolk. He was at one time H.M. Ambassador at the Court of Madrid. Ann was Charles’ first wife and was buried at Fincham on July 29th 1584. Sir Charles, as he became in 1603, lived on in Fincham until after his wife’s death. Significantly he had purchased the Fincham estate from Ann’s brother William. Thomas’ widow, Martha was still living in 1577. She married twice more. William Fincham was the next owner of Fincham Hall after his father died in 1551. Thomas made a will which Blyth had difficulty in reading because it was much damaged. He saw that Thomas disposed of his real estate to his wife- William his heir being only an infant. It consisted of the Fincham property and manors or lands in Brancaster, Burhham Deepdale, Burnham Norton, Burnham Sutton and 18 other parishes mentioned. Then comes his Testament in which he bequeaths ‘to all the poor folke of Fyncham 40 shillings, to my beloved wife all the goods and utensils in my house in Fyncham and in Burnham Deepdale, to the common box in Fyncham £6 8s 4d., to my son William 500 good mother ewes at his age of 21 years, (and) all the goods and utensils in the chamber above the chapel, to Ann Fincham my daughter 300 sheep, 20 cows and a hundred marks on the day of her marriage. To my little cousin George Walker £6 8s 4d. To my cousin of West Wynch my cloth night gown furred with conye, (rabbit skin) and to Mr Yelverton my father-in-law my bay gelding. This will shows Thomas was a wealthy man – his son William would inherit a great deal.

****************************************************************************************

William Fincham

William was aged two years and 45 weeks at his father’s death in 1551. Blyth found that his wardship and marriage were granted, February 17th 1553, to Sir Edward Warner Knight. The deed attached to this sums up the value of his estates at £94 16s 9d. It would be interesting to know the circumstances around his sale of his Fincham estates to Charles Cornwallis, his brother-in-law. This was in 1572 when William had turned 21 and ‘come of age’. Blyth never found the Will of William, the last occupant of the family to live in Fincham Hall and conjectures he never made one having sold the estate and left Fincham in 1572. Blyth found evidence he was ‘defunct’ before 1586, in an ‘Old Deed in the possession of Mr J.B.Barsham’ (a Fincham resident during Blyth’s time). There is one plausible explanation for William selling his estates around 1572. From the age of two when his parents died he may have formed a close relationship with his sister and, subsequently, Charles Cornwallis and was quite happy to sell his estates to them. About the same time Blyth records ‘he married Audrey daughter of Sir Thomas Lovell, Knight, of Harling.’ The Lovells were an ancient family in Barton Bendish. Rather like the Fincham family their influence stemmed from connections made after the Conquest when lands were given as rewards for service to the monarch. Andrew Lovell was living in Barton Bendish in the second half of the 13th century and his descendants prospered there for some centuries, as did their close neighbours the Finchams. No doubt there were quarrels sometimes but their status in society must have meant much contact. Anyone who wants to examine the Lovell family tree will find much material in Blomefield’s History of Norfolk. Suffice to say that through various descendants, often named Thomas, William or Ralph, we come to Ralph Lovell who was Lord of Lovell’s Manor, in Barton Bendish, in 1474. Ralph, whose wife was named Joan, had three sons who all became knights. Sir Gregory was the eldest son and heir and was knighted fighting for Henry Tudor at the battle of Stoke in 1487 and Sir Robert, the second son,was knighted at the battle of Blackheath in 1497 when Henry VII’s troops defeated a Cornish army. The third son was Sir Thomas Lovell who fought at the Battle of Bosworth with Henry Tudor, rose to be his Chancellor when he became Henry VII, and was in fact Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1485 for over thirty years, an extraordinarily long time. He continued to thrive and hold high office under Henry VIII only to become less powerful when Thomas Cromwell’s influence increased. When he died in 1524 he was very rich with many estates all over England. He had contributed to the building of Caius College, Cambridge and built a gateway for Lincoln’s Inn. He also built a manor- house at East Harling. Sir Thomas died childless and left the bulk of his estate to his nephew Francis. Francis was succeeded by his son, Sir Thomas Lovell (died 1567), who was followed by his son, Gregory Lovell (1522–1597). William Fincham, according to Blyth, married Audrey Lovell, daughter of Sir Thomas Lovell of Harling. It’s not entirely clear which this Sir Thomas of Harling (East Harling) was. The most likely one is the Sir Thomas who died in 1567. William was born c.1548 and so if he married Audrey about the same time as he sold the Fincham estates in 1572 that would be consistent with her parents being Thomas and Elizabeth. The fortune that Thomas the Chancellor left Francis, father of this Thomas, would have gone far even with many children inheriting. The Lovell’s of East Harling and Barton Bendish were of the same family and with so few differing first names it is difficult to be quite sure who is who but the wealth passed on by the Chancellor Lovell is indisputabe.

So a possible scenario is that William Fincham, born 1548, lost his parents when only two years old and had a sister Ann who married Charles Cornwallis. When he came of age he fell in love with Audrey, sold his considerable Fincham estates to his brother-in-law, and went off to live with Audrey in, no doubt, considerable style. If his parents had lived until he was an adult then perhaps his connections to the village would have been strong and he may not have sold the estate. So far no trace of William or Audrey has been found after he left Fincham.

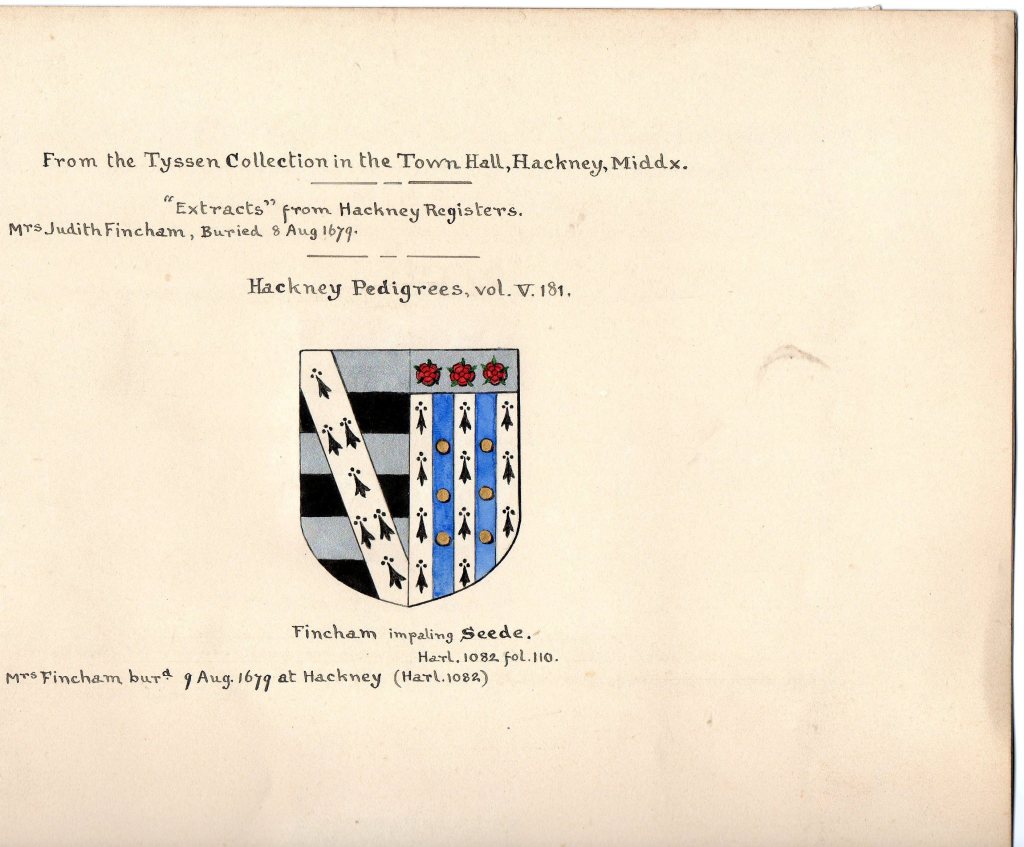

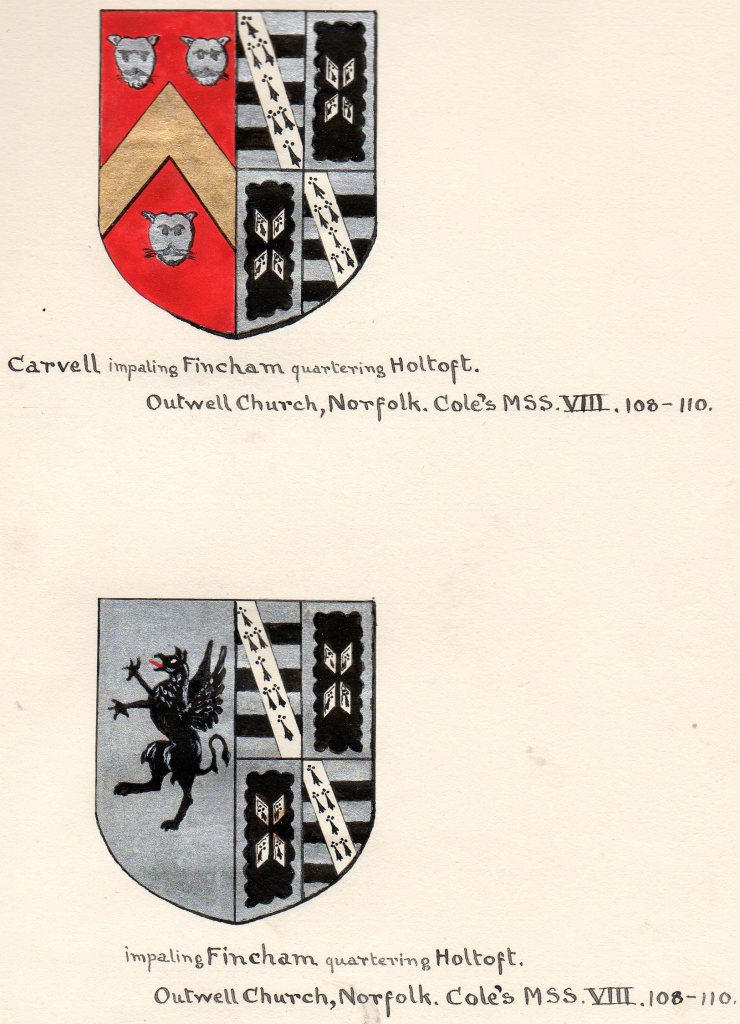

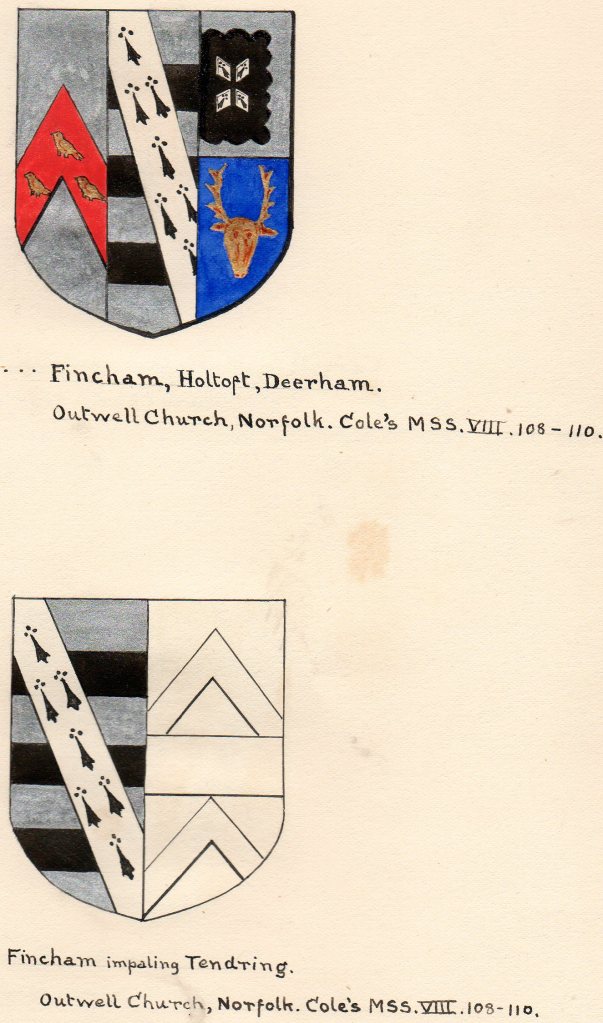

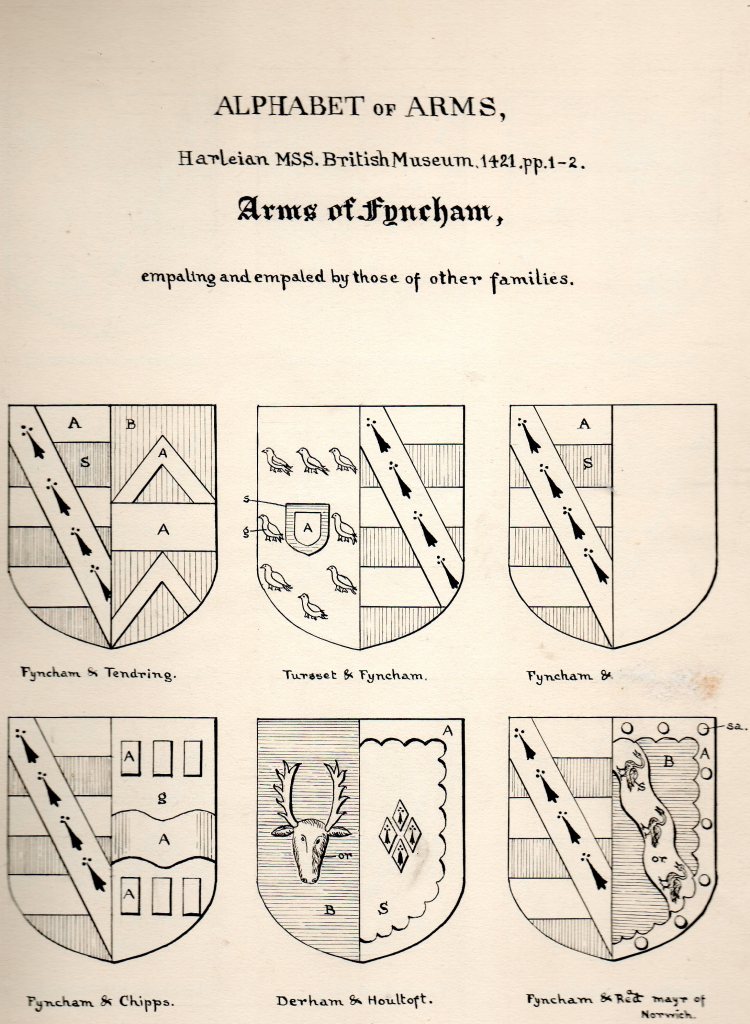

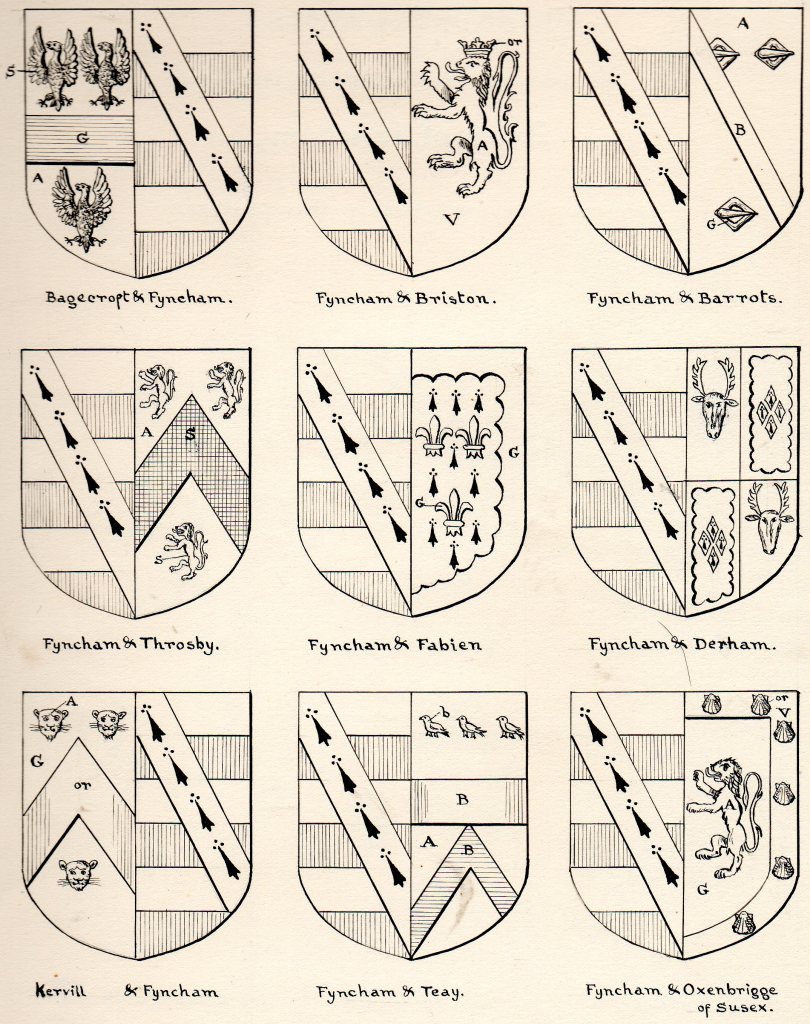

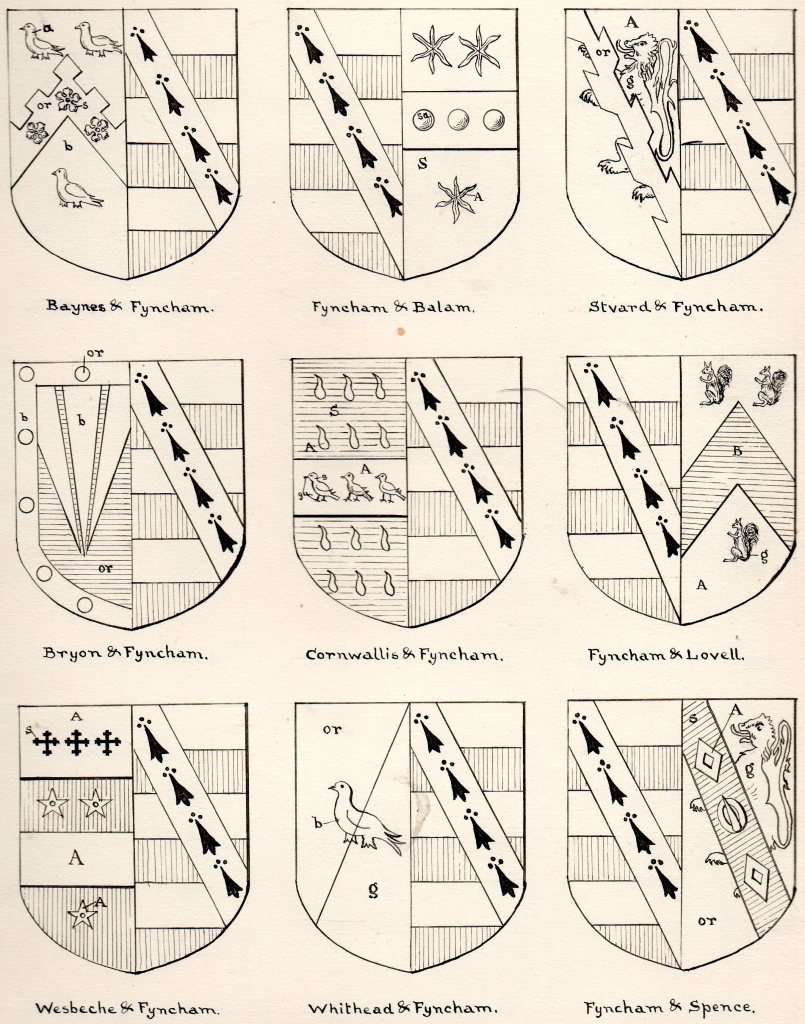

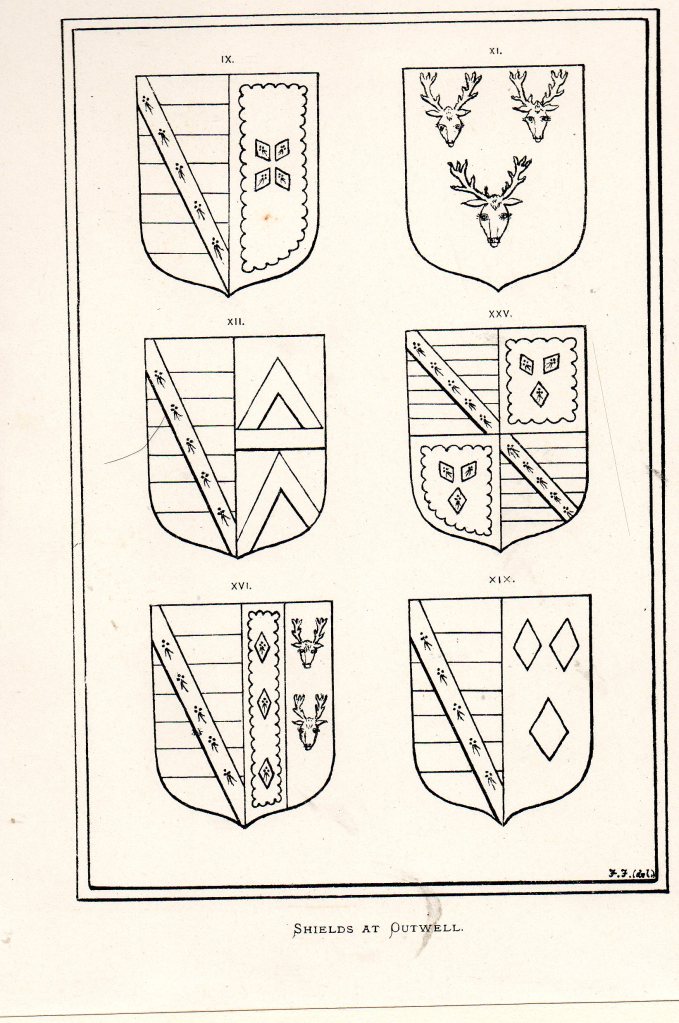

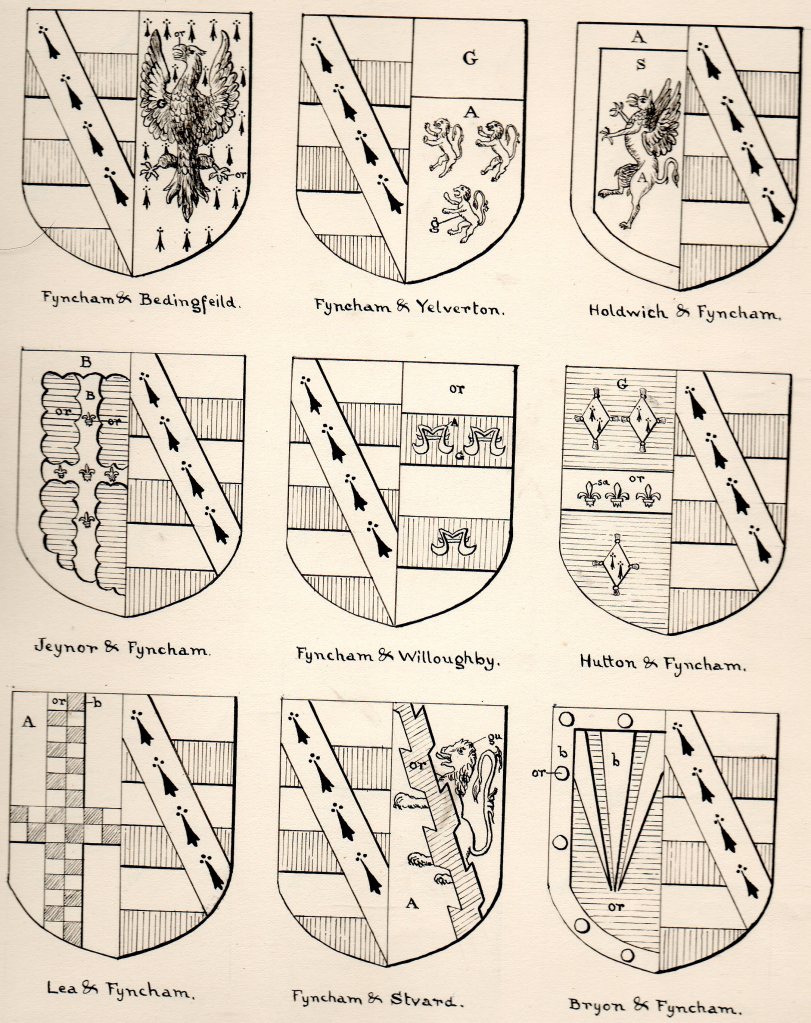

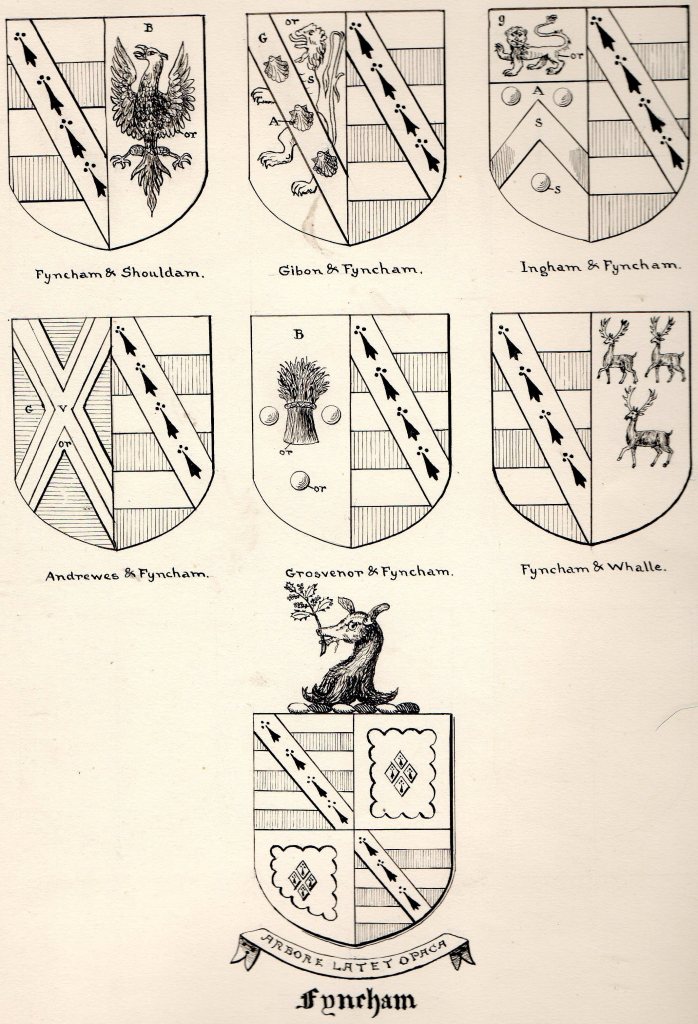

When two families were united through a marriage a joint Coat of Arms could be made. Here are some from a ‘Hackney’ collection. Outwell church is mentioned.

The next are Coats of Arms from the Harleian Manuscripts

Names to note are Cornwallis, Lovell and Bedingfeild which feature in the story of the family above. Other names can be found in the Fincham family trees in Blyth’s book. These Coats of Arms really emphasise the importance of the Finchams over many centuries. They married into so many upper class families.

THE TREE HIDES IN THE SHADOWS