A fine example of the diversity of building materials in the village. A wall of Flint and Chalk clunch beside an extended end gable of galleted flint set into Carstone and brick. The façade of the house has been faced in Cambridge yellow brick and re-roofed in slate. In the background is the flint and imported limestone tower of St Martin’s church.

West Norfolk is an area that is quite distinctive in its use of building materials as the underlying geology provides some of the hardest and softest stone available anywhere in the country. Flint is remarkably hard and extremely durable, as a result it has been in used in walling from the earliest of times. In unworked nodules it is a heavy and strongly weather resistant and in a worked knapped form it provides a high status decorative flush work that may be seen in the tower of St Martin’s Church. The village sits on a field of lower middle chalk that has been a source of cheap building stone for thousands of years. Chalk is so soft that it may be cut into blocks with a domestic hand saw and as a result it is susceptible to weathering that will cause it to crumble over time. Many chalk walls were once lime washed in order to provide a degree of weather protection.

From the very earliest of times the roofing material of choice within the village was of course reed or wheat straw and this material remained in use even into the early years of the 20th century. In 1908 at least three houses in the high street retained in thatch. This material requires constant vigilance and it may have become less prevalent in the village following the events of 13th August 1761 when a fire in a blacksmith’s shop spread to the Crown Inn and then to several houses, four barns and several outbuildings. The summer weather would have dried the thatched roofs allowing the fire to spread quickly and it is probable that at least two of the buildings affected would have been the cottage adjacent and the church barn that once stood opposite the Crown Inn.

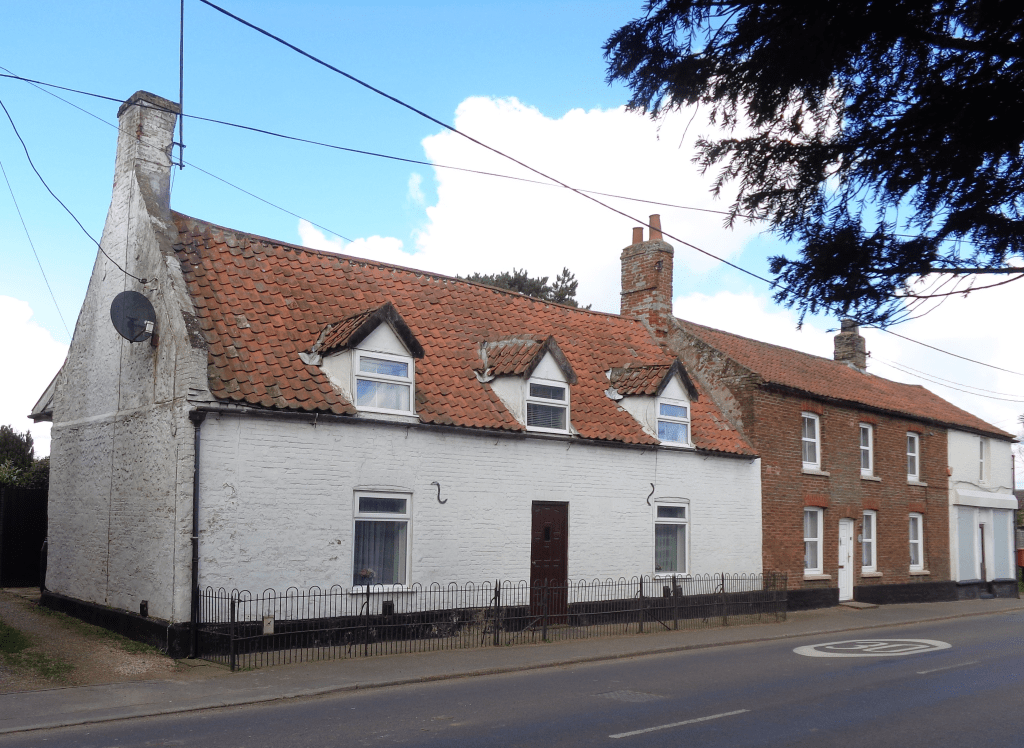

Pantiles were first introduced into Norfolk from the Netherlands in the early 17thcentury and from that point there was a gradual adoption of this roofing material in the village as home owners decided to replace thatch with a more durable and fire resistant material. Clear evidence of this change may be seen in a number of houses in the high street.

The front of Crown Cottage showing the lowered roofline as thatch was replaced with hand made pantiles. The building was originally two workers cottages and the outline of the two doors can be seen on either side of the current front door.

The village has a good stock of buildings that wear their history on their facades. The difficulty of finding matching building materials has often resulted in a patchwork of infills and extensions that clearly show how some of the oldest houses have evolved. Many have a mixture of flint, chalk, carstone and brick that tell the story of the structure. Some of the earliest houses in the village were originally low single story structures that have subsequently been extended to the rear and refaced at the front. A number of houses also show evidence of building up whilst still displaying their original roof line.

The side elevation of Lovelock Cottage showing flint galleting to the original chalk and carstone single storey cottage. The original structure is then built up with random rubble and brick infill and extended at the rear to increase the footprint of the house. Finally, the roof of the extension is raised in brick. The building is shown in its earliest form on the 1772 map and the façade shows a blocked window that resulted as a saving from Window Tax (1696 – 1851)

One of the oldest properties in the High Street is Nelson’s House, an early 17th century originally timber framed house house that was replaced by brick in the 18th century. This listed building retains its 17th century windows and staircase. This structure is one of the many in the village that incorporates recycled Barnack Stone from the demolished church of St Michael. Until the 19th century, the expense and difficulty of transportation of building materials meant that any building materials that became available locally would soon be salvaged and reused in other buildings. The specially “imported” Barnack stone is only the most obvious example of architectural salvage within the village. It is quite possible that the stone to be found in a many of the old buildings has been salvaged from other much older structures on one or more occasions.

The White House is another 17th century timber framed house fronted by an early 18th century façade. This is another example of a house that illustrates its origins as later brickwork indicates an additional story as the house has grown and a façade showing that there were two dwellings at one time.